Clash Quest, the Unofficial Postmortem

Written by Laura Taranto, Javier Barnés, and Anette Staloy. Make sure to listen to the podcast below to dive even deeper into Clash Quest.

In games, like in real life, we often have more to learn from misses than successes. And when the lesson comes from a company known for its superb quality like Supercell, there’s even more to think about.

A few weeks ago, the Clash Quest team announced that they were going to discontinue the development, after a soft launch of 16 months. The game was first available in the Nordics, followed by a quick rollout to the Philippines, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and Singapore.

A cancellation shouldn’t be too surprising, since Supercell has never been shy about its philosophy of ruthlessly killing games that fall behind their billion-dollar hit expectations. And this confirms that the rule applies even to their three new games based on the Clash IP.

Clash Quest is Supercell’s most recent attempt at disrupting the puzzle category through titles like Smash Land, Spooky Pop, and Hay Day Pop, each of them trying to achieve success from different angles. All of them are fun, innovative, and well-crafted games that ultimately failed to find a suitable market spot -- a story that is quite similar to Clash Quest.

This raises the question: After accumulating knowledge in the category from so many projects, what was missing this time? Is there a critical lesson that Supercell overlooked?

Despite significant innovation in terms of gameplay (Smash Land, Spooky Pop) and metagame systems (Hay Day Pop), Supercell has not been able to release a hit in the puzzle category.

In this article, we will speculate about the reasons leading to the cancellation of Clash Quest, review their update strategy during the soft launch, and discuss what lessons this game may hold for Supercell -- and for anyone else aiming to disrupt the Puzzle genre.

Welcome to our unofficial postmortem of Clash Quest.

Clash Quest 101

In terms of gameplay, Clash Quest can be categorized as a blast-based midcore Puzzle game with some RPG components.

The meta is somewhat similar to Best Fiends or Supercell’s previous Smash Land: A saga-like map with levels that players must complete to progress, while simultaneously upgrading a series of characters (more on this later).

The gameplay resembles Legend of Solgard and Might & Magic: Clash Heroes (Nintendo DS):

The objective of each level is to defeat enemy units located on the top of the screen.The bottom part of the board is filled with friendly troops that players can tap like in a blast game. The tapped unit, as well as any adjacent one of the same type, will then attack one after another and the empty spaces will be filled with reinforcements.

Players lose the level if they run out of troops and reinforcements.

To play levels the players have to use 1 Quest Energy, capped at 12, and refilled over time. When running out of Energy, there was an option to use Quest Tokens, bought from the store, or earned through free Daily Deals. In the final update, this energy system was completely revamped.

Levels have a degree of strategy. On every move, the player needs to consider:

The unique attack behavior of each troop. For example, Archers avoid obstacles and shoot at the nearest enemy on the board, while Princes attack in a straight line and damage the first thing they hit.

The column that units will attack, aiming to destroy the specific enemy units that will attack sooner, or deal the most damage, killing friendly units before they can attack.

A damage bonus based on how many units of the same type are activated (blasted) in the same action. This means that the player has to carefully build up big combinations on the board, at the right time, to max out the damage output.

The usage of spells, tactics, and magic items: Mechanics reminiscent of classic puzzle game boosters, but with more limited uses. Examples include an area damage bomb, a spell allowing to swap units on the board, and a magic item that randomly shuffles friendly units.

Despite these strategic elements, luck also plays a big (often critical) factor, due to the randomness of the troops starting position, the randomized reinforcements spawning, and the limited ability of the player to manipulate the board.

We think that luck likely overweights skill in Clash Quest and strongly damages any kind of deeply strategic-oriented playstyle. It’s difficult to execute any plan. For example, the inability to separate troops means that you may be forced to use them all in a single attack, whether it makes sense or not.

Because of that, the main factor to win levels that players can control is to upgrade their units: Troop stats can be increased by spending gold and shards (units elixir that can be obtained in crates or the shop). Contrary to other puzzle or Clash games, the player can’t offset at all a handicap on upgrades with skill.

Later down the road, Clash Quest also added Runes (passive perks) and Items (customizable boosts that allowed specialization) to units, which added extra depth to the mix. They were additional layers of things to collect and upgrade.

But despite these extensions, Clash Quest upgrade and progression systems felt more shallow than in other Puzzle RPGs.

Perhaps the critical reason for that is that - contrary to most Puzzle RPGs - in Clash Quest players are not able to collect and select teams of unique heroes on each level, which instead are pre-determined for the level.

This design decision cripples the collection factor that fuels most games in the Puzzle RPG category (liveops, grinding…) and made the game much more linear (and casual).

What killed Clash Quest?

We think there are 2 main reasons why Clash Quest did not reach world launch:

#1 Not engaging for the existing audiences

Clash Quest is too casual to engage midcore audiences long-term, while also too complex to appeal to and engage casual audiences. This positions it in a niche market space that does not scale to the level that Supercell would need to achieve a massive hit.

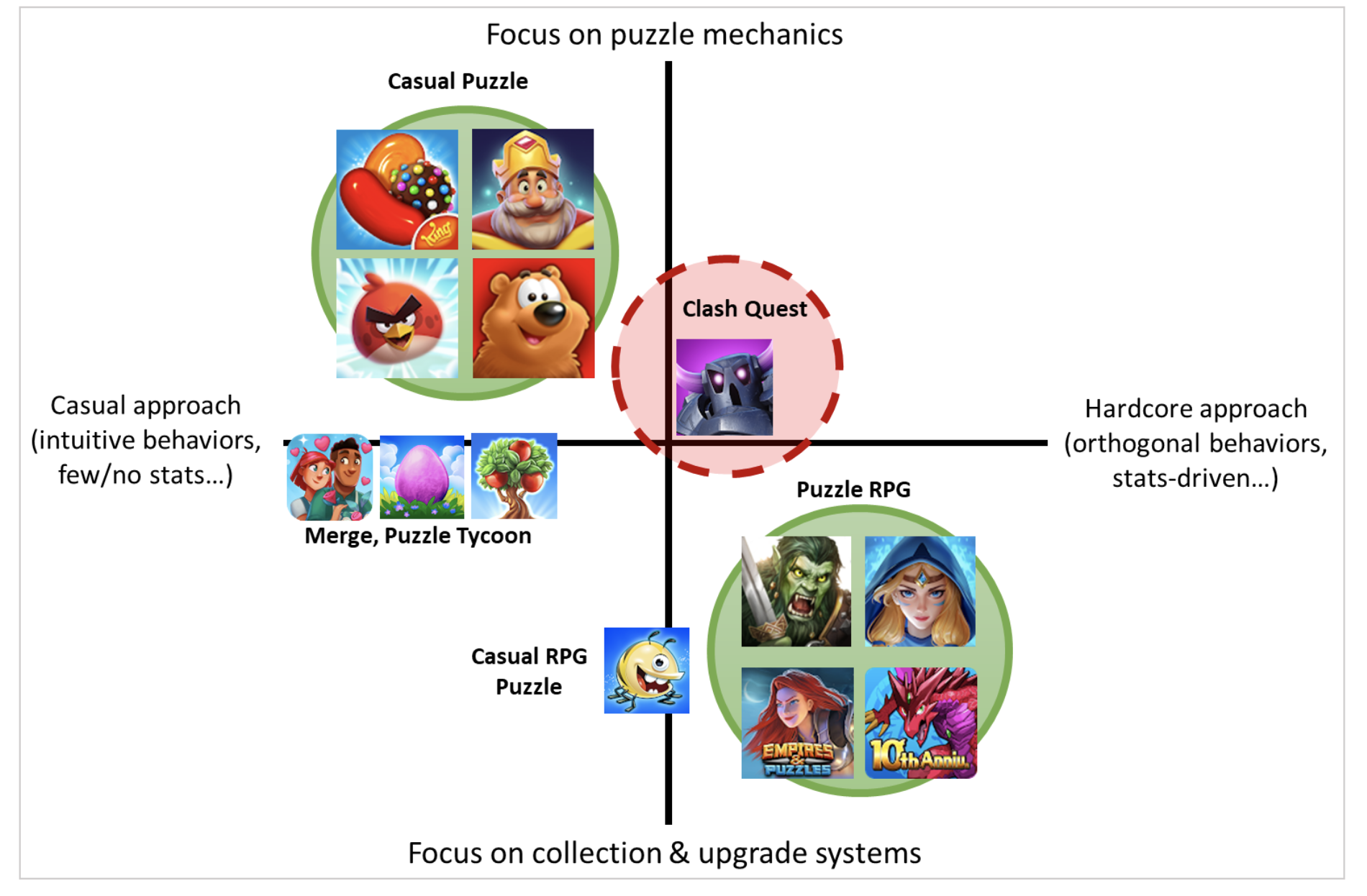

In our opinion, the high potential market spaces in the Puzzle category are:

Casual puzzle games that provide an accessible experience. They are often targeted to non-gamer demographics or players that want a lighter gaming experience (they can be enjoyed while doing something else or in public transport). The strategy and player focus are on solving the puzzles by doing moves to manipulate the board to create boosters and destroy blockers… Gameplay is primarily based on skill and luck. And the meta component outside the main puzzle gameplay is more limited.

Puzzle RPGs where the real meat is on the RPG and hero collection mechanics. These games have more in common with RAID: Shadow Legends or Galaxy of Heroes than with Candy Crush. The puzzle component is lighter and acts as a replacement for the turn-based RPG combat system. Piece manipulation and board composition are not the main focus since both randomness and skill are negligible compared to the weight of character upgrades.

(Obviously, this is a simplified categorization. Some Casual Puzzle Games have more meta depth than others, and in some Puzzle RPGs some of the combats may have a stronger tactical component, but we think it describes the two main archetypes of experiences).

Contrary to that, Clash Quest is a game with a Puzzle RPG exterior (stat-driven game, very orthogonal unit behaviors, upgrade systems…) but where the focus is on solving puzzles and the puzzle mechanics themselves, not on the collection and upgrade mechanisms.

As a consequence, Clash Quest was not engaging for Casual Puzzle players (that would expect a more approachable experience), not engaging Puzzle RPG players (that were expecting more focus on collection and upgrade systems), and not engaging for midcore Clash IP fans (that didn’t find enough PVP and gameplay depth, and strongly disliked the randomness factor).

Clash Quest's actual target seems to be a sort of casualcore segment which - if it does exist to a meaningful size - it’s already tapped by the existing games, leaving no opportunity for an intermediate product to grow.

#2 Bad retention, low LTV, high CPIs

As a consequence of the previous point, we think that Clash Quest never achieved good enough retention on any of its targetable audiences. And because of that, it was never able to build a big enough LTV to face the insanely high CPIs of the puzzle or puzzle RPG genres.

The low LTV (which we attribute to the low retention primarily) is noticeable if comparing RPDs between different titles from the Puzzle Category: Clash Quest places below well-known casual puzzles like Homescapes and Royal Match, and the difference is even bigger if compared to Puzzle RPGs like Funplus’ Call of Antia.

Interestingly, Clash Quest RPD is quite similar to Legend of Solgard, a game comparable in terms of gameplay, and which likely suffers from similar issues of lack of audience long-term appeal.

A low Lifetime Value per User (LTV) puts more weight on having a low Cost per Install (CPI) to get a positive Return Over Advertising Spending (ROAS). This is extremely difficult to achieve in the puzzle genre due to the strong competition to acquire users.

In theory, an IP could help lower a bit the CPIs. But we think that in this case, the Clash IP didn’t help at all because:

Casual players that recognized the IP (and those that didn’t recognize it and just looked at the screenshots and videos) likely considered the game too hardcore and unfamiliar.

It attracted mainly midcore and hardcore audiences, which found a game that wasn’t made for them.

Additionally, the Puzzle genre is not suitable for brand/content creator marketing, one of the key Supercell marketing and distribution strengths. In the past, Supercell has relied on content creators' marketing to bring audiences to their games (incentivizing through, for example, allowing payers to donate a % of their spending to their favorite influencers). But the content creator audiences likely weren’t very receptive to Clash Quest, which is not as fun to watch due to the lack of PvP and has way less mastery depth. Instead, the Puzzle genre is more suitable for standard user acquisition, a topic where likely Supercell is less experienced than specialized companies.

In the Clash Quest reddit, the developers themselves blamed the disappointing retention and problematic ROAS for the decision to cancel the game:

[...] while profitability is just one facet [of why we cancel a game at Supercell], it's not the most important one. Player retention metrics over a certain duration of time is one of the most important ones. How long players stay after downloading the game after 1 day, 3 days, 7 days, etc. are some of the more important ones.

[...] While we did limited amount of user acquisition, it's a genre that's flooded with games that spend millions of dollars on UA. UA is probably one of the biggest drivers of puzzle games as puzzle games tend to be more PVE/single player experiences. And because of the RNG nature of puzzle games it's also why you don't see a lot of puzzle games with many content creators or dev videos. So the approach to a successful puzzle game is quite different than how you'd approach a game like Clash of Clans or Brawl Stars.

The full post can be found here. (The bold emphasis is ours).

How did they try to solve it during Soft Launch?

Judging by the updates history, we think that the team was aware of the retention problem and at first, tried to pivot Clash Quest to become more engaging for midcore players and Puzzle RPG fans by increasing both the strategic depth and the amount of content.

From May 2021 to February 2022, updates added new grinding side activities (Dungeons, Shipwrecks), new upgrade systems (Runes), a new type of booster (Magic Items), Clans, and several new troops and spells and new levels and enemies.

It seems that the objective was to boost retention (and perhaps also spending) by providing players with new mechanics and units to upgrade and master, as well as provide a regular flow of new levels to progress through.

The Clans feature deserves special mention since Supercell is well known for using social competitiveness in several of its games to boost engagement and spending in several of their games. Although, we believe that given the single-player and PvE nature of Clash Quest, it’s unlikely that Clans alone would have been able to turn the game around.

But if there was an opportunity in strong social features, it was missed by a problematic execution: Clan discoverability was rudimentary and often lead to empty clans, players had no real reasons to chat and coordinate with each other, could not exchange resources, and the clan activities didn’t bring meaningful social experiences. It was all about completing challenges playing on your own, and doing your one-attack-per-person daily chore.

After these improvements didn’t deliver the expected results, the team made a big attempt to increase retention by going in the opposite direction with the last big update, which seems aimed to casualize the game by removing gear options, revamping blocker systems like energy and stars, add new game modes and gameplay objectives, and more narrative.

This last update noticeably damaged the revenue of the game (and likely also the long-term retention since it involved a progression reset for players) and was probably what convinced the team that making Clash Quest Supercell’s next hit was not possible.

In the last update, Clash Quest attempted to smoothen progression by revamping the star system. Instead of collecting a certain amount of stars to progress, you played through the main quest, one level at a time until the Boss level at the end (closer to casual puzzles). After a successful Boss fight, the player was shipped off to the next island.

Why did these changes not work? What could they have done instead?

These sorts of questions seem much easier to answer when you’re outside of the ship, free from the responsibility of steering its direction, and have the advantage of hindsight. But here we go.

We think that if product market fit and retention were the main issues, then surface-level changes were unlikely to yield major improvements.

During most of the soft launch, Clash Quest added several features aiming to make the game more engaging: New upgrades, Clans, Side Quests... But arguably, none of these changes radically changed the basic experience or the core gameplay.

That sort of approach would have perhaps been good at increasing monetization. But if the gameplay wasn’t engaging enough for the audience, it’s difficult that an incremental strategy can radically uplift retention.

If the core was not resonating with the audience, perhaps the best way to address it was to rework the core gameplay. This is a high effort, high risk, high reward decision, so any team should think twice and thrice before going for it. But after a few months of new features, new content, and balance changes that didn’t do the thing, it’s hard to argue that perhaps to solve the problem, Clash Quest had to take a step back and review the foundations.

For example, to improve strategic playstyle, Clash Quest perhaps could’ve tested allowing players to manually arrange the board at the start (or bring it pre-selected like a deck) and preview the units that would appear in the next move.

Or if wanting to deepen the casual puzzle aspect, perhaps having endless reinforcements with a limit on total moves.

Allowing to manually select the troops for each level could’ve also empowered collection and liveops mechanics.

What can we learn from Clash Quest?

#1. Product/market fit is the key. And in Puzzle, it’s difficult to find.

Historically, Supercell has been most successful when attacking new and unexplored entertainment spaces (tactical strategy to mobile with Clash of Clans, tactical CCG with Clash Royale, top-down shooter MOBA with Brawl Stars) or by disrupting stagnant genres (Hay Day).

The Puzzle category is likely an unsuitable target for truly disruptive products, and not suited for innovation in Supercell's sense. The reason is that it's a red, ultra-competitive, galvanized market with constant innovation and iteration.

The huge competitiveness in the Puzzle category means that there are more chances of succeeding by understanding the existing rules and mastering them -- not by breaking them.

If we look at some of the latest successful cases in the category (Call of Antia in Puzzle RPG or Royal Match in Casual puzzle), we find that both deeply understand existing audiences and were able to deliver an experience that satisfies their needs better than the competition.

There doesn't seem to be significant potential for discovering new audiences or bringing new audiences to the puzzle category, since any high-value niches are likely already colonized by the more generalist competitors. Additionally, a significant part of the audience of the category is formed by older demographics and audiences not familiarized with games, and this audience may not be very receptive to projects that reinvent the wheel and force them to learn things from scratch.

For that reason, we think that Supercell has more chances of succeeding in Puzzle (particularly in casual audiences) through their M&A, where they’re funding companies that take a more traditionalist approach to the genre.

#2. A great customer experience offsets reputational damage from potentially controversial decisions.

The Clash Quest team has set the bar high for the rest of the industry when it comes to interacting with the community.

For starters, the team was active on the game’s social networks (Reddit and Discord), being transparent and humane in communications.They also regularly produced a Captain’s Log, a sort of dev diary where the community could hear the devs' thoughts on the changes they were doing, the reasons behind them, and what were they considering as next steps.

But the point where they really excelled was in managing the hard decisions. There is no way to make everyone happy when a game resets the progression or announces that the show is over, but the communication and specifics of the execution can generate a huge difference.

On top of having great transparency on the reasons behind the decisions, the team was generous with the reset progression refunds, and the user experience chatting with the Goblin bot to transfer funds to another Supercell game after the announcement has been surprisingly nice.

#3. Celebrate the effort and lessons from what do you, regardless of the results. The only “failure” is not to try.

Shout out to the Clash Quest team: They had the courage to try something new and different in one of the reddest ocean categories of the market and ultimately delivered a fun and beautifully crafted game.

This is probably the biggest lesson everyone can take away from Clash Quest: It is OK to try new things and not achieve the desired results. It’s part of the path. Nothing has ever been achieved by not trying. And while it’s hard to make the call to stop working on something, especially something you’ve invested a lot of time and love into -- quality is worth killing for.

Just learn and live to try again.

Suggested Side Lectures:

Written by Laura Taranto, Javier Barnés, and Anette Staloy