10 Years of Excellence - Deconstruction of Supercell

Supercell is one of the rare companies that doesn’t try to beat the competition; rather, it tries to beat the high score set by its own prior games. To date, Supercell has created multiple genre-defining games and generated billions in revenues -- all with little more than 300 employees (!).

However, the latest numbers released by Supercell confirmed that its portfolio has been declining for three years in a row and that new games have not been able to offset this trend. As a result, some are wondering if Supercell’s “haydays” are behind them.

Our short answer is no. Out of all the gaming companies out there, Supercell is one of the few capable of shipping consecutive monster hits. However, to return to a growth path, Supercell should also consider additional levers to complement its high-risk, high-reward development strategy:

Strengthen Live Services and performance marketing to stabilize its existing portfolio, while continuing to drive growth through new releases

Leverage M&A to add new titles to their portfolio or new capabilities to scale how they operate existing games. While Supercell has been active on this front, in reality the company has spent four years and around $100M with little to show for.

The objective of this analysis is to provide a prediction on Supercell’s future and, where possible, make suggestions on their path forward. To do so, we will deconstruct Supercell’s strategy, portfolio, culture, and M&A efforts. We will also discuss how the market has evolved in the last 10 years and discuss the implications of this evolution for Supercell.

This post is the collaboration of several Deconstructor of Fun members. All the data is derived from Sensor Tower’s fantastic data plarform. Cover image: Talouselämä.

#1 THE HIGH-RISK, HIGH-REWARDS STRATEGY

Most mobile gaming companies bet on incremental innovation as their gateway to success. They make marginal improvements to an existing game, hoping to convince enough players to switch to their game. Other companies take elements from benchmark titles and combine them with a new theme to reach a new audience or carve out a niche within an existing audience.

There are only a handful of companies that try to disrupt the market by creating new genres or redefining existing ones. Disruptors rely on gut feeling, an extremely high level of talent, and... a lot of courage to pull off this high-risk, high-reward strategy. Supercell has clearly mastered this strategy so far, since they can be credited for creating 4 genre-defining hits: Hay Day, Clash of Clans, Clash Royale, and Brawl Stars. This is an astounding achievement as most disruptors are lucky to produce a single hit of that magnitude in their lifetime.

These are just some of Supercell’s incredible achievements so far:

$12B in total gross revenues over the last 6 years (mic drop)

Its first 4 games passed $1B in lifetime revenues (and Brawl Stars will soon join the club)

Long “staying power” of its games, as they remain relevant for years

Clash of Clans is one of the most successful mobile titles ever (revenues estimated ~$6.5B)

Global footprint (in 2019 ~40% of revenues came from the US and ~15% from Asia)

Well diversified portfolio across genres (from simulation to build & battle and MOBA)

Currently only 320 employees to achieve all of the above

However, no matter how big of a fan of Supercell you are (and we at Deconstructor of Fun for sure are), you can’t overlook the numbers. In the last few years, Supercell has been on a gradual decline, as existing titles have slowed down and new launches haven’t been able to fill the void.

Supercell’s Financial Performance in 2016-2019 (source: www.supercell.com)

#2 HISTORY & PORTFOLIO ANALYSIS

It all started with Hay Day. Launched in May 2012, Supercell’s first game redefined the farming genre on touchscreen devices. The game took over the market from Zynga’s FarmVille, which at that time launched FarmVille 2 on Facebook. In its ~8 years, Hay Day has been a stable business with an estimated $2B+ in lifetime revenues.

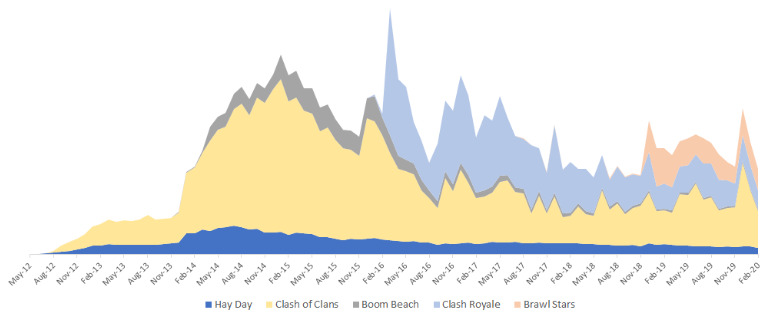

Supercell’s bet on touch-screen devices continued with Clash of Clans, which quickly became a global hit. In particular, it’s truly impressive to see its acceleration in 2014, driven largely by the introduction of clan wars. This is one of the cleanest examples in the industry of the “power of social”: it took Clash of Clans from ~$50M to ~$200M/ month in a few months.

Supercell’s Gross Revenues by game over 2012-2020 (source: Sensor Tower)

On the back of Clash of Clans’ success, in late 2013 Supercell released Boom Beach, a “PVE version of Clans”. To date, Boom Beach is the only game Supercell ever globally released with a differentiation strategy . While Boom Beach never reached Clash of Clans’ performance, it topped $1B in lifetime revenues.

In 2015, Supercell had its best year with $2.33B in gross revenues, propelled by Clash of Clans’ breakaway success. Then, in March 2016 Supercell launched Clash Royale which smashed every record with $1B in gross revenues in its first year. As a result, 2016 was another amazing year for Supercell with $2.30B in revenues.

However, the revenue composition of the company in 2016 was very different from 2015. Clash Royale’s success was likely fueled also by a cannibalization of Clash of Clans: Clans’ decline in Q1/Q2 ‘16 suggests that several players tried Clash Royale and then did not return to Clans.

In 2017, Clash Royale’s revenues started falling quickly and by late 2018 were ~50% of their 2016 peak. Some argued that launching a game with the same IP and a gameplay that appeals to similar players was net negative for Supercell over time. Instead, we think that Clans would have declined even without Clash Royale (albeit at a slower rate) due to the “law of gravity” that all mobile games face after launch and, therefore, that Clash Royale was net positive.

Nevertheless, since every single game released after Clash of Clans had a lower RPI, it is important for Supercell to carefully consider the impact of new launches on existing titles - and in particular the risk of existing players migrating to those lower monetizing titles.

Revenue per Install of Supercell games in their first 12 months after launch (source: Sensor Tower)

Finally, in late 2018, Supercell launched Brawl Stars, with a different IP and a very different gameplay. Brawl Stars is an action-packed, esports-focused MOBA and thus it didn’t cannibalize existing games: in fact, Clash of Clans remained stable, Clash Royale continued its rate of decline, and Supercell’s total revenues in 2018 grew.

Supercell’s Genre Defining Mega-Hits

Clash of Clans’ breakaway success is obvious from all angles. Whether we’re looking at the (estimated) $6.5Bn in lifetime revenues, the game’s consistency at the top of the grossing charts or the way it has demolished all the new entrants attempting to take a piece of the gigantic revenue pie.

Clash of Clans has shown unprecedented staying power by staying in the top 10 grossing since 2012 (data: Sensor Tower).

Clash of Clans’ success has been built on 4 elements:

Compelling gameplay: Whoever thinks that mobile games are not “deep enough” clearly hasn’t played Clash of Clans yet. This game packs some of the best balanced, nerve- wracking, strategic gameplay on a mobile device. It manages to be relevant to players who seek an extremely high skill cap experience as well as to players who just want to have fun and blow up the opponent’s base. Clans also has an extremely smooth progression. Every town hall unlocks new troops and defenses, encouraging players to learn new attacks, while managing complexity.

Transformational social experience: As discussed, the introduction of Clan Wars was the tilting point that transformed Clans from a great success to one of the top mobile games ever. Clan Wars provided new reasons to play the game and to continue chasing progression: sharing a common goal, coordinating efforts, and having deep discussions on attack strategies. This allows top players to “carry the team” and showcase their skills. Over time, Supercell wisely built on social, adding new flavors to it (e.g., Clan Games, a cooperation-based PVE experience, and a league system with progression).

Very deep economy: If Clans’ gameplay and social experience fuel a never-ending desire to progress, its economy provides a quasi-never-ending progression curve. Maximizing your progression takes years (even for high spenders) and for most players it represents an aspirational goal more than a real target. The game achieves this by gradually increasing upgrade costs (and can get away with it since most upgrades feel meaningful) and by releasing new town halls, unlocking new levels of buildings and units (plus new ones). The true masterpiece here is that Clans continuously moved the goalpost in a way that players look forward to (to progress more…) vs. a negative experience.

Live services: Over the years, the game hasn’t lost its step and has continued to provide fresh content regularly. Even better, the team has showcased a holistic focus on the game:

Masterfully balanced the gameplay with regular nerfs/buffs, refreshing the meta

Designed for both elder and new players, often forgotten by mature games

Took risks (e.g., the Builder Base and its new core loop and gameplay) and spent real development time on quality-of-life improvements

Stayed at the forefront of innovation (e.g., introduced battle pass relatively early and with one of the finest implementations in the mid-core space)

We encourage everyone to watch the fantastic presentation by Eino Joas, Game Lead of Clash of Clans as he explains the challenges and the team’s approach to solve them.

Prediction for Clash of Clans:

Based on the current trajectory, we expect that Clash of Clans will continue at a steady course generating about ~$1B in 2020 as it did in 2019 (up from ~$800M in 2018) due to two reasons:

Clans’ players are extremely loyal, having invested years (and money) in the game and, more importantly, having become part of its strong social network

The game is undoubtedly run by one of the absolute best groups of professionals in the industry.

But there may be a curve-ball coming. In case Supercell releases a third Clash title with much stronger emphasis on 4X elements, Clash of Clans will experience decline driven by cannibalization.

When Clash Royale was released back in 2016, Tencent’s CEO, Mr. Lau, was apparently such a fan of the game (among millions of others) that Supercell’s CEO, Ilkka Panaanen, reported:

Mr. Lau (CEO of Tencent) had just dropped out from Clash Royale’s global top-100 players leaderboard, and it was almost impossible to get his focus back to the topics we had to discuss.

from an article in the The Wall Street Journal

Clash Royale’s explosive initial success (~$1B in its first year) and cumulative revenue of in excess of $2.5B to date lured many top publishers to try to break into the Tactical Battler sub-genre created from scratch by Supercell (e.g., Netmarble’s Star Wars, Nexon’s Titanfall, and EA’s Command & Conquer). Yet, no matter what IP or gameplay modifications the rivals made, none of these well-crafted competitive games was able to carve enough audience to even continue live services, let alone compete against Clash Royale. With its 90%+ revenue share, Clash Royale has proven to be an unassailable stronghold and effectively defines this sub-genre. However, since 2017 revenues have been declining rapidly: -35% in 2018, and -15% in 2019.

Clash Royale: Worldwide Gross Revenues by year ($M) (Source: Sensor Tower)

So if Clash Royale is such a dominant title, why did it drop so fast?

In the Clans’ section we discussed how the game creates a “never-ending desire to progress”. Clash Royale doesn’t quite achieve this. In other words, Clash Royale lacks the spend depth of Clans, due to some of the factors that make it so successful earlier on in the player’s life cycle:

High skill cap with a ladder-based progression: The gameplay is amazing, but very complex and requires time to master. Because the measure of a player’s success in the game is defined by an individual PVP ladder (while in Clans it’s all about the Clan Wars and the social dynamics explained earlier), players are disincentivized to switch decks and try new cards for fear of dropping trophies.

Diminishing returns from upgrades: At first, upgrading cards feels exciting, as it’s cheap, frequent, and material. However, players eventually experience declining returns from their investments, as upgrading costs grow exponentially but their cards’ power progression is linear. So, players see that their key cards reach a “good enough” level, and their desire to spend slows down. Also, several competitions take place at a low card level cap (“tournament standard”) easily achievable in a few months. This is admirable as it celebrates skills, but lowers the incentives to upgrade cards (vs. Clans’ current war league system encourages players to upgrade as much as they can).

Card level caps: Cards are capped at a certain level. When spenders max out those cards, they don’t really have an incentive to level up other cards, unless they are proficient with them as well (i.e. whales’ spend is skill-capped!). Clans, instead, keeps moving out the goalpost by releasing new town halls that unlock new levels of buildings, heroes, and troops.

To their credit, the Clash Royale team has tried to solve this problem by introducing several creative and risk-taking innovations, such as:

New interesting cards to switch up the meta and new challenges (e.g., touchdown) to encourage players to enjoy more cards than the ones currently in their deck

A clan-based competition, where players need to be familiar with/ invested in more cards to help their clan (interestingly, social here hasn’t worked as well as it did in Clans)

An extremely fun and chaotic 2v2 PVP mode, where players can freely experiment with new cards, since losing doesn’t cost any trophies

Trading tokens, making the most expensive cards more easily achievable

Unfortunately, the game’s continued decline suggests that these innovations did not fix the economy problem. We’ll explore these points (and also focus on the different outcomes of Battle Pass in Clash of Clans vs. Clash Royale) in more depth in an upcoming article.

Prediction for Clash Royale

Unless Clash Royale addresses its economy, it will continue to gradually decline in the future (e.g., 10-15% in 2020). Some of the ideas that the team could consider include:

Introducing card restrictions, taking a page from Hearthstone’s or Magic The Gathering’s playbook (i.e. the “standard” format)

Innovating with new game modes to encourage players to develop a broader collection. One of these could be a re-imagined version of Auto Chess (though they would first need to solve the monetization issues of the new genre, as discussed previously)

Instead, it’s unlikely that they will follow Clash of Clans’ example and introduce higher caps for existing cards, because of how vanity is tied to reaching the max level of a card.

After a long and difficult soft launch with multiple pivots, Brawl Stars launched to global success in 2019 and raked up ~$0.5B in its first year. This shows Supercell’s tenacity and ability to adjust. As a result, Brawl Stars is set to become Supercell’s 5th game to reach $1Bn in life-time-revenue.

In addition to the massive revenue stream, Brawl Stars enabled Supercell to increase its penetration of a new audience in terms of both geography (Asia Pacific and, in particular, South Korea) and demographics (younger players). This is very important for Supercell as it allows the company to grow while limiting cannibalization risks to its existing portfolio.

The problem is that this new audience Supercell connected with tends to be quite fickle and prone to moving en masse to the next hot thing. (Something Fortnite has learned as of late.) As a result, despite the strong start, Brawl Stars’ revenues have been steadily declining.

So what’s the problem? We think that the revenue decline is driven by two factors:

Lower “loyalty”: Brawl Stars has a simple, skill-based gameplay, with a fun factor that scales up when friends play together (ideally nearby). The social gameplay and the cartoonish art style helped the game become popular with the younger Gen Z audience. However, Gen Z is an unpredictable audience: they are all about the hype and will move to the next hot game without a second thought (something Fortnite has learned lately)

Lower monetization: Brawl Stars has the lowest RPI in Supercell’s portfolio. This is driven both by its economy (less deep vs. Clans or Royale) and its young audience.

Just like Fortnite, Brawl Stars needs to win back its audience every month. To do so, Supercell focuses on fresh Live Services content and on investing in esports, partnerships, community, and other top-of-the-funnel marketing campaigns. However, we believe that to reverse the rapid revenue decline, Supercell will also need to unlock a higher monetization ceiling and develop a deeper economy.

Prediction for Brawl Stars

We believe that 2020 Brawl Stars will reach new highs with the launch in China. After all, it is a Tencent game (though interesting enough is by Tencent and Yoozoo in China). Nevertheless in the long-term we believe that Brawl Stars’ decline will likely continue. We don’t foresee Supercell making radical changes to the game to deepen its economy. Also, given Supercell’s desire to remain small, the team may be hard pressed to drive bold in-game innovations as well as promotions outside of the game while maintaining the content treadmill needed to support live services.

Prior to hitting consecutive home runs with mid-core games, Supercell had also been waving its magic wand in the farming space. Launched in 2012, Hay Day changed the way players engaged with this type of games in terms of platform (Hay Day was first to mobile) and gameplay (e.g., the Order Board revolutionized farming games). Nearly eight years after launch, Hay Day is still the most iconic farming game for touchscreen devices (in particular on iPad).

Despite being the highest grossing farming game for a long time, Hay Day has been gradually losing market share in the last 2-3 years. In particular, Hay Day’s revenues started to decline in 2018 when Klondike’s Adventures (from Playrix’s Vizor) was released. The decline continued in 2019 when Playrix’s Township, after having been neck and neck with Hay Day for years, started to scale up UA leading to a situation where Township is twice as big as Hay Day.

Crafting/ Tycoon sub-genre: revenue share by game over 2017-2019 (source: Sensor Tower)

While Township’s installs have significantly accelerated in the last year, Hay Day’s downloads have been flat/slightly declining. This is likely because the game receives very few, if any, installs through performance marketing, which is usually the case for many so-called ‘legacy titles’.

Township, Klondike, and Hay Day: Revenues and Installs over 2017-2019 (source: Sensor Tower)

Prediction for Hay Day

Due to Township’s and Klondike’s growth, Hay Day is now the 3rd player in crafting sub-genre, and may drop to 4th, depending on how Farmville 3 fairs when it launches in 2020. Still, Hay Day’s decline is quite slow when considering the competition’s growth. This implies that Hay Day’s core players retain well and that it will be hard for Township and Klondike to “steal” them from Hay Day.

Lastly, since Hay Day doesn’t seem to rely much on performance marketing, the increasing CPIs (driven by the “install war” started by Playrix) have little impact on the game’s performance. Yet, without marketing support, the gap between Playrix’ titles and Hay Day is going to grow.

What about Hay Day Pop?

In the first quarter of 2020 Supercell soft-launched their second title with a puzzle core - Hay Day Pop. On paper, Hay Day Pop seems like a smart move from Supercell: it’s a puzzle game for a simulation audience with a familiar character that got a face-lift. Hay Day Pop is Fishdom meet Hay Day with a tile blast mechanic. By all accounts, it is a good game. It’s just not a great game. It represents the type of incremental innovations that other gaming companies focus on instead of the “oh wow” disruptive innovations that Supercell used us to.

FarmVille extended its IP to puzzle back in 2015. It was a solid game but it couldn’t stand up to King’s saga titles. In 2020 Hay Day Pop is entering less concentrated yet even more competitive puzzle genre.

Looking at Hay Day Pop’s design elements, there are several unconventional, fun improvements to both core and meta - such as the use of battle pass as the core progression vector. On the other hand, the theme, art style, and UI are all proven, smart re-uses of existing elements from other games. Also, the lack of narrative in a game like this makes it a bit boring and mechanical: there’s no silver lining behind what you’re doing. In a sense, it's just like Fishdom, which is the weakest (still highly successful) and oldest puzzle game in Playrix’s portfolio.

However, given the spot-on execution, this game is not going to perform badly, if (and that's a major unknown right now) Supercell can get low-enough CPI. Otherwise, Supercell would need to improve the game’s monetisation, which doesn’t seem to be in the cards given its current form. Also, this would require standing up a team to drive Live Services events to sustain engagement and monetize this game. This will lead to a bigger team. And a bigger team tends to lead to a question - should we even launch this game and commit to 10 years of content cadence for a top 200 game?

Prediction for Hay Day Pop

Due to its current low level of innovation, we don’t see Hay Day Pop disrupting the puzzle genre. However, with a compelling narrative and a creative marketing strategy Hay Day Pop could become a solid puzzle game that can generate significant revenue - though at a lower scale than the other games in Supercell’s portfolio likely missing the company’s ~$1B “minimum” watermark.

Oh, the first Supercell puzzle game? Please check our deconstruction from years back:

Supercell's Spooky Pop and the Six Rules of a Hit Puzzle Game

SECTION 3: THE (NOT SO) SECRET SAUCE

source: Supercell - our story

So, how did Supercell create so many genre-defining games? Well, it’s not a mystery. It's basically all that Ilkka Panaanen talks about in interviews and writes about on his blog. Based on his words and on, more importantly, on the company’s actions, it is evident that their Supercell’s strategy is designed to achieve three objectives:

Create an environment that fosters innovation

Create a culture of constructive confrontation where internal development has to go through a gauntlet of peer reviews

Give team the autonomy to make key decisions about their game - including the decision to kill their own games

These three objectives aim to generate as many shots on goals as possible, which is key, since most ideas are destined to fail. At the same time, these limit the consequences of failed ideas as much as they can, which enables Supercell to try again with limited impact.

At first glance, it may be easy to overlook how difficult to achieve these objectives at the same time truly is. What it takes to achieve one (i.e. passion and creativity) is quite different from what it takes to achieve the other (i.e. rigorous analysis and a firm hand in pulling the plug). Most gaming companies usually are good at pursuing at most one of these goals. Some companies are great at ideating, but they “toy” with ideas for too long and then take forever to execute them - often, having to course-correct mid-development because the project scope got out of control. It’s also common for companies to miss the window of opportunity as the market evolves and their game is no longer relevant. Instead, most of the companies focus only on (so-called) safe, short-term bets and shut down their own creativity to start with.

Supercell’s culture enables them to pursue all of these goals; specifically, these three elements of their culture create the secret sauce:

Mission: Making games “for as many people as possible, that will be played for years, and remembered forever” -- this is very different from a financial goal

Ownership: Supercellians can team up organically to pursue an idea and are in charge of making the hardest decisions related to their game (including killing it, if it doesn’t work)

Small size: This enabled them to reduce unnecessary bureaucracy, be extremely selective in hiring (t-shaped generalists instead of specialists), prioritize only their best development ideas, and reshuffle development teams easily when new ideas don’t work out. However, their small size also poses key challenges, which we’ll discuss later...

That’s basically it. Seems strange, doesn’t it? After all, most companies have an aspirational mission to be the best, and pretty much every company says that they foster a culture of ownership or that they operate in a lean way.

So what’s different at Supercell? Well, they actually live their culture and all their decisions seem consistent with that culture. A few examples from Supercell’s CEO’s blog or other articles can bring this to life:

Ilkka defines himself as being the “least powerful CEO in the industry”

“Some Supercellians were openly against Brawl Stars” (the key word here is openly)

“The company had a discussion about their size, as many employees felt that it would be hard to maintain their culture if we grew too fast”

Regarding the shutting down of Rush Wars, Ilkka said that he’s “proud of the decision the team made” and primarily empathized with the team for the hard, but right decision

Top management continues to pay outrageous government taxes (Finland’s tax rate goes well above 50% for top earners), setting an example of fairness and transparency

But before you decide to adopt their culture as well, consider two important elements of Supercell’s culture that are often overlooked: high turn-over and very frank feedback.

Turnover: Supercell is notorious here. Word on the street is that in some years up to half of the new hires were terminated during their first 6 months. Which you have to put into perspective considering that Supercell hires only the absolute top talent in the World. This creates a culture of extreme pressure to deliver demanded by one’s Supercellian peers instead of the management. However, Supercell does not have a toxic culture: it’s just a culture where you have to hyper-deliver all the time or leave.

Feedback: By “feedback” we mean a ruthless level of feedback, especially for games in development. The bar for what looks and feels good is extremely high, while the bar for giving feedback is low. Playing games in development and providing teams with feedback is not only celebrated but nearly mandated. After all, when your peers tell you “do better”, it feels way more powerful than hearing it from executives.

SECTION 4: IMPLICATIONS OF MARKET EVOLUTION FOR SUPERCELL

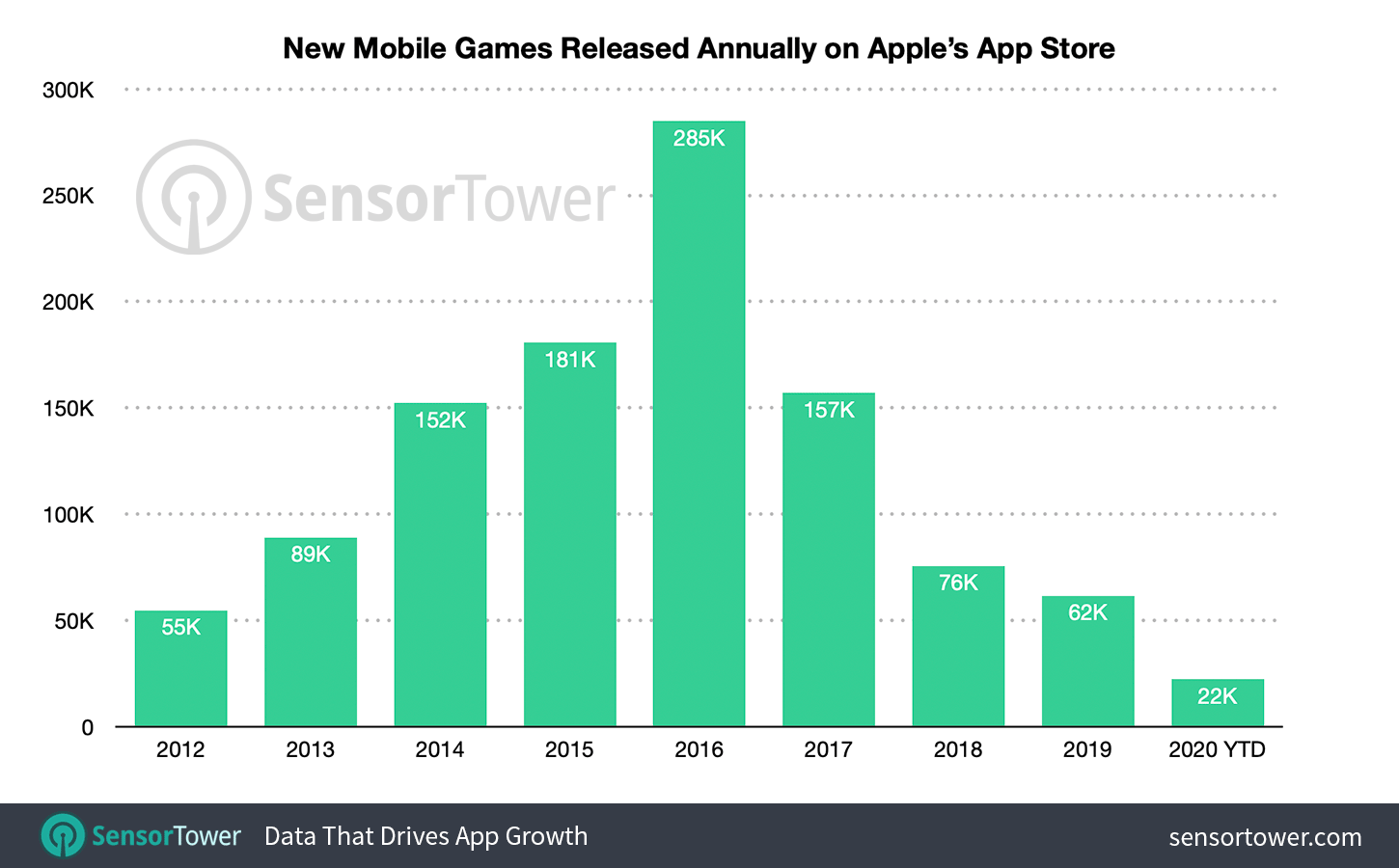

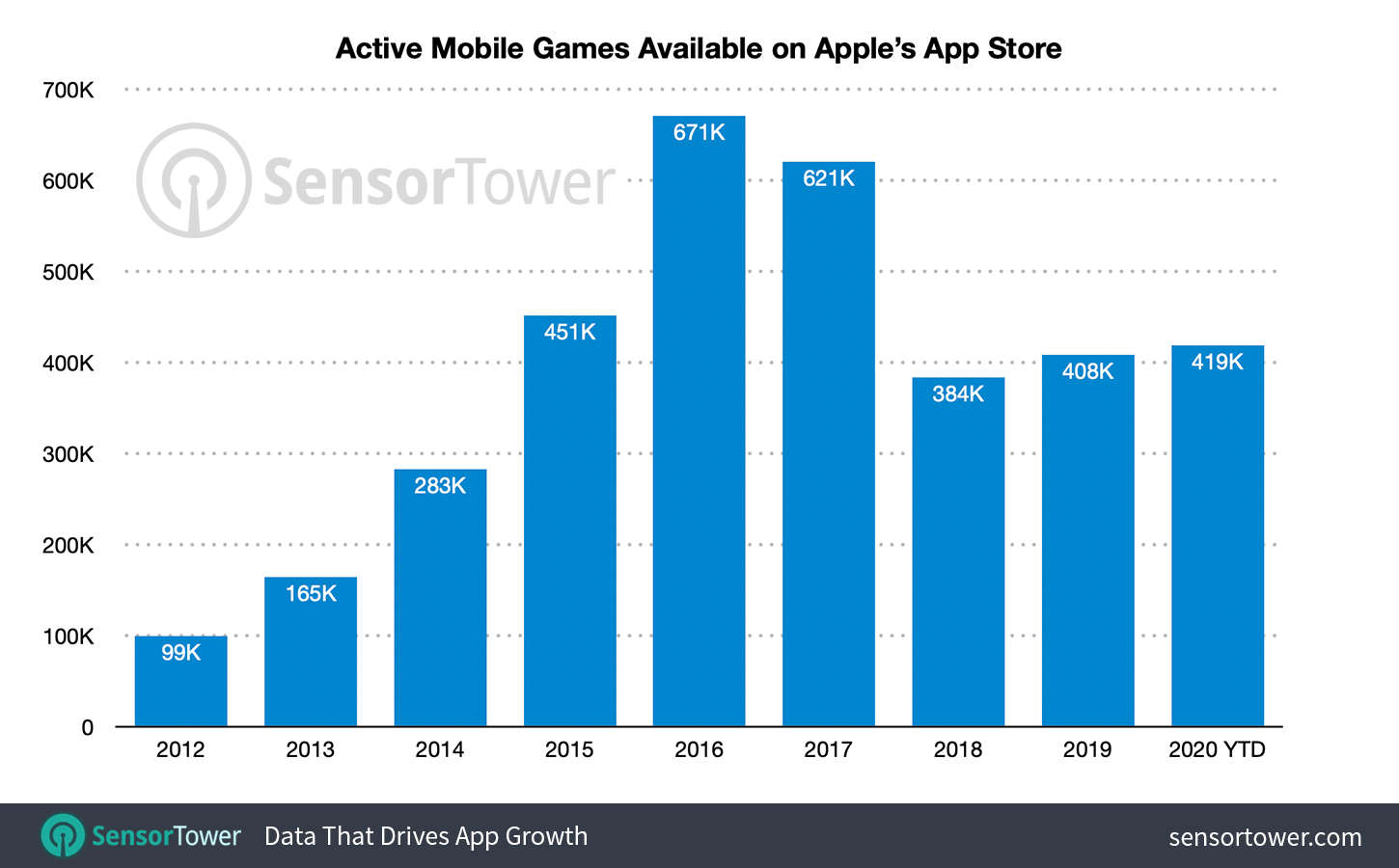

In the last few years, the mobile games market has changed radically. The amount of new games entering the market has plummeted and there have been fewer new games entering and sustaining their position in the top grossing charts.

The market has matured with less games entering the market…

…and the amount of games in the market stabilizing.

The maturation of the market is driven by the evolution of the Free-To-Play business model itself and the increased sophistication of game developers, such as:

Spend Depth: Most of the growth (at least in key markets) comes from increasing paying players’ spend instead of more players entering the market. The implication is that winning requires creating deep economies to drive LTV and systems to retain existing players

“Winner-take-all” dynamics: Competition is increasingly a “winner-take-all” game across genres, where top ~3 competitors typically take up 60-80% of the market, leaving little room to smaller players. Just look at our 2020 predictions with a breakdown of top competitors by genre

As can be seen from all the red, Mid-core category is highly concentrated. Supercell is actually one of the biggest winners controlling three sub-genres with Clash of Clans (Build & Battle), Clash Royale (Tactical Battlers) and MOBA (Brawl Stars).

First-mover advantage: Related to the prior point, being one of the first few companies to enter a genre has become even more important, because the first few games have the best chance to create high switching costs for players through:

a) Social networks: e.g., when all your friends are playing Fortnite, why would you switch to another Battle Royale game, unless its gameplay is meaningfully different or you like the IP much better?

b) Progression: i.e. when you have invested a lot of money and time to progress down the (power/ skill/ vanity) curve, why would you switch to another similar game, where you have to re-learn and re-earn everything from scratch?

One of the key implications of this trend is that publishers now have a shorter time window to launch a game in a new genre and win. In other words, development cycles need to be faster.

Live Services are vital: Most Live Services today are optimized to entertain players more deeply than in the past and end up taking up more of players’ time, making it harder for new games to “steal” players. Having strong Live Services today is key to reach the LTV needed to afford ever -growing CPIs. However, live services are expensive and require different skills vs. system design.

UA can turn into a knife fight: Incumbents can literally “suck the air out of the room” by engaging in UA wars, where only the highest LTV games can afford to pay for the growing CPIs and afford the years-long payback times. This means that entering a space with lots of established competitors is even harder than in the past.

As a result of these trends, most successful mobile games publishers have four common elements:

A successful game publisher aims to constantly overachieve in all four of the elements. Supercell has for sure been excellent in all of the elements. Though in recent years the publishers hasn’t always been able to keep up with modern Live Service requirements. The reason being that live games have become increasingly content driven requiring ever larger team sizes. And as we know, Supercell’s foundation contradicts the notion of big teams.

Implications for Supercell

Most of the trends above imply that hoping to break into the top 100 chart with incremental innovation is increasingly hard. Instead, Supercell’s approach to making genre-defining games is better suited at reaching commercial success than launching, say, another Clash Royale clone. Obviously, Supercell’s strategy is not for everybody, as it requires extremely high design talent, creativity, and a risk-taking, long-term focused mindset (by the way, this is why we’re not bullish when Supercell works on incremental innovations like Rush Wars and Hay Day Pop).

On the flipside, Supercell seems to be struggling with Live Services, as discussed with Brawl Stars. Their small size is in stark contrast with the need to sustain existing games, while staffing up new teams to plan for the future. Simply put, one big update per year is not sufficient to retain your most engaged players.

More broadly, Supercell’s desire to remain small and nimble is already being challenged by operating in several locations (e.g., Shanghai and San Francisco, in addition to Helsinki). And as discussed in Eric Seufert’s article, we can argue that Supercell’s approach to separate marketing from product is a practice of the past.

If growing way beyond 300 employees is not in the cards, then outsourcing and externalizing could be the answer. Supercell has already taken steps in this direction, but doing more of this will require more processes, which will lead to more management, which could lead to loss of ownership and speed -- which fit Supercell’s culture like garlic fits into vampires' diets.

Another approach would be to off-load legacy titles like Boom Beach to Space Ape for live services. It would be a win-win, though it’s highly unlikely that Supercell considers this.

Supercell is know more for its top-of-the-funnel marketing than performance marketing. With games that have such broad appeal like Clash of Clans, this approach makes sense.

Finally, it’s the UA resources. When it comes to money, Supercell has thousand time more than it needs. When it comes to people, Supercell can hire them. When it comes to influencers, Supercell has been investing into this since 2012. And when it comes to organics, everyone loves Supercell and will install their game. Nevertheless, Supercell’s capabilities on the performance marketing side might be limited. It’s been a while since Supercell has been recognized for performance marketing excellence, as the company has switched its focus to top-of-the-funnel channels (TV, events, billboards) and influencers. In a way, Supercell’s marketing strategy feels more like “carpet bombing” than a tactical operation. Their approach suits big launches for wide audiences, but seems less geared towards finding pockets of new players with targeted performance marketing campaigns.

SECTION 5: M&A STRATEGY

While Supercell has been smashing it with creating games, its M&A efforts have been lackluster. After 4 years and ~$100M invested, Supercell has little to show for it. This is because Supercell doesn’t seem to have a compelling M&A strategy.

In general, M&A strategies are built around acquisition of synergies and purchasing of scale. The two are often supported with smaller investments into future bets.

In 2016, Supercell started investing into other companies. In a typical Supercell fashion, they did it with no fanfare, which resulted in even more interest because of the limited context around their plans. In 2017, Mikko Kodisoja, co-Founder of Supercell, said to Venture Beat:

When we look for external teams and studios, first and foremost we’re looking at the team. The team should have a similar kind of culture to what we have at Supercell, so there can be full ownership for the teams that develop the games….

We want to diversify our portfolio and invest in teams that do something different from us…

Their vision has to align with ours. We want to make games that last for decades. People play them and remember them. All the studios we’ve invested in have that same kind of mentality

Mikko Kodisoja, Supercell

To summarize, this strategy can be interpreted like this: Supercell invests into companies that look, sound, and feel a lot like them. Companies that dream of becoming like Supercell.

The good part about this strategy is that it’s simple and it focuses on finding a cultural fit, which makes any cooperation much more easier down the line. It’s easy to know if you’re jiving with a target company, as you’re looking for the same characteristics that you already possess. Also, there are a lot of companies that do their best to mimic Supercell. And why not? After all, the aspiration of building a great (top grossing) game with a small team in an organization where teams come first is every developer's dream.

However, on paper, Supercell has so far invested into companies that have much to gain from Supercell, but that Supercell has little to gain from -- both in terms of M&A strategy and results produced. In reality, the situation is even worse, as the acquired companies didn’t seem to have received the “cheat codes” they were hoping to obtain from Supercell. And with only 300 people, there is limited time to spread the magic around.

To understand this better, let’s look at the investments made by Supercell so far:

2016: ~$10M in Frogmind (51% stake); ~$4M in location-based start-up Shipyard

2017: ~$60M in Space Ape (62% stake)

2018: ~$5M in Trailmix (ex-King team); ~$6M in Redemption Games; ~$6M in Everywear Games (used to be known as Apple Watch games company)

2019: ~$4M in Luau Games; ~$1M in Wild Games; Ritz Deli (amount unknown)

These companies have produced limited results to date, e.g.:

Frogmind released two great looking games (Badland Brawl and Rumble Stars) and used Super Scale to scale their games. On paper, this seems to show Supercell’s ability to help their portfolio companies. However, the real challenge for developers lies in scaling a game when you don’t have the war chest nor the experts to drive and sustain growth.

Space Ape was known for their lean live services. Since the Supercell acquisition, Space Ape has publicly discussed about on how they’ve switched to a much more creative way of working after. Yet the developer has released only Fastlane having been forced to cancel Rumble League (a very Brawl Stars type of a game) after an extensive soft-launch period.

Redemption Games received strategic investment from AppLovin. A publisher that has a track record of growing they portfolio companies. What can be derived from this is that investment from Supercell helps to bring in talent and hone in company culture as well as the ways of working. But when it comes to growth, Supercell just doesn’t seem like the right partner for a small to mid-size developers.

The other issue is exiting. After all, starting a company is taking a major financial risk from founders’ perspective. VC will push you to grow and eventually sell or IPO when the price is right. Supercell doesn’t need to. For example, who’s going to buy the rest of Space Ape? Those are likely the stocks owned by the founders and the key staff. With Supercell owning the majority, the upside for Space Ape folk seems to be somewhat obscure. And with no clear upside looming in the horizon, maybe the effort might not be at the same level as with a typical startup? On the other hand, Supercell does bring unrivaled level of stability, which makes it much easier for smaller developers to hire top talent.

Looking forward, Supercell has three options to fix its M&A strategy:

Invest more into portfolio management / developer relations. This means setting up a structure for active knowledge sharing on all fronts of development as well as marketing with their current and future portfolio companies.

Focus on investing only into truly independent and accomplished companies. Peak Games, Tactile Games, and Lilith -- just to name a few. These companies don’t need babysitting and they can help Supercell to grow in turn.

Stop M&A efforts. The current approach feels a bit like a distraction. Supercell should do everything like it builds its games - full focus, best talent, aim only at the top!

SUPERCELL in 2020 and Beyond

Attempting to drive disruptive innovation comes with significant uncertainty in terms of timelines and outcomes. As discussed, Supercell is one of the few companies that is best positioned to generate genre-defining hits in the mature mobile gaming market. However, despite Supercell’s approach to kill games with less than staggering potential as fast as possible, their creative process can’t exactly be put on a conveyor belt to deliver year-on-year revenue growth. But the good news is that the outcomes of their games have been nothing less than outstanding so far.

So, it is not very useful to look at Supercell’s short-term financials to determine their ability to create “unicorns” in the long term. The real metrics to determine this should be tied to the decisions they make and to the new games they launch. So far, instead of turning conservative and guarding their market share by making incrementally ‘better’ games, Supercell has stayed on the offensive and continued to launch only genre-defining hits. Killing Rush Wars is a perfect example of this determination (let’s see what happens with Hay Day Pop).

Nevertheless, Supercell does have a few opportunities to boost their performance beyond their current approach on game development:

Increasing their focus on Live Services to sustain existing games

Stepping up their efforts on performance marketing

Pursuing M&A as a lever to grow both audience and revenues

As Supercell considers these (and other) opportunities, it will have to wrestle with how to scale the company for success without losing the culture that led them to where they are today.

We’d like to conclude our analysis with a bit of a thought exercise. Imagine for a moment an alternate universe where Supercell was never acquired and where the company had chosen to aggressively pursue acquisitions in addition to organic growth. In this alternate universe, Supercell would have likely acquired Small Giant and/or Gram (maybe even Peak and Playrix). Supercell would have been a totally different company not only in terms of size, but also culture. While it wouldn’t likely become the company developers around the World look up to today, one thing is for sure - we wouldn’t be discussing whether Supercell’s best days (in terms of revenue) are behind and what the publisher should do to get back on the growth track.

Let us know if you agree or disagree with our thoughts.

- Deconstructors of Fun

----------------------------

This analysis is written by Miska Katkoff and Giovanni Ducati with the help from compact but powerful Donstructor of Fun group.

For more content about Supercell please check out some of our previous analyses: