The 7 Steps to Successfully Greenlight a Game with an IP

This is a guest post by Andrew N. Green, who is currently Co-Founder and COO of Knock Knock. Prior to Knock Knock, Andrew was Head of Business Operations at TinyCo where he built, launched, and operated games like Family Guy: The Quest for Stuff, MARVEL Avengers Academy, and Harry Potter: Hogwarts Mystery.

“Beyond study and instrumentation, there is instinct.”

- Annorax*

Creating a new F2P mobile game is riskier than it’s ever been. The majority of F2P mobile publishers are prioritizing the improvement of live operations processes for existing products over the creation of new products to generate more reliable revenue and to control costs. It’s more important than ever to protect the hard earned spoils of successful live operations – both by spending wisely and by protecting product leadership from the randomization that comes with new product concepting. As a result, the process to greenlight new products can, and in many places has, become slower, more measured, as well as increasingly risk-averse.

M&A is becoming an increasingly attractive arena for growth, but building new teams and products will remain an important investment at organizations of every size. Making the right choices at project greenlight can be the difference between a successful future vs. a destabilising force to your studios and portfolio health. How do studios of all sizes invest in new products prudently in today’s games market?

I Need a Process (sung to the tune of “I Need a Hero”)

As is the case with every facet of product development and live ops, running the right process is key. In live ops, these review processes are well-defined: systems and economy design, merchandising, UX, data analysis, and sprint planning for features that drive KPI improvements, better player segmentation, and improved UA funnels are the foundation of F2P mobile product success. This is the quantifiable stew that creates the nutrition needed for product survival and growth.

However, in the earliest stages of new product creation there are many subjective creative decisions that are fundamental to product success. These subjective criteria can’t always leverage data to help guide the decision-making process - this is the primordial ooze where breakout hits begin their evolution.

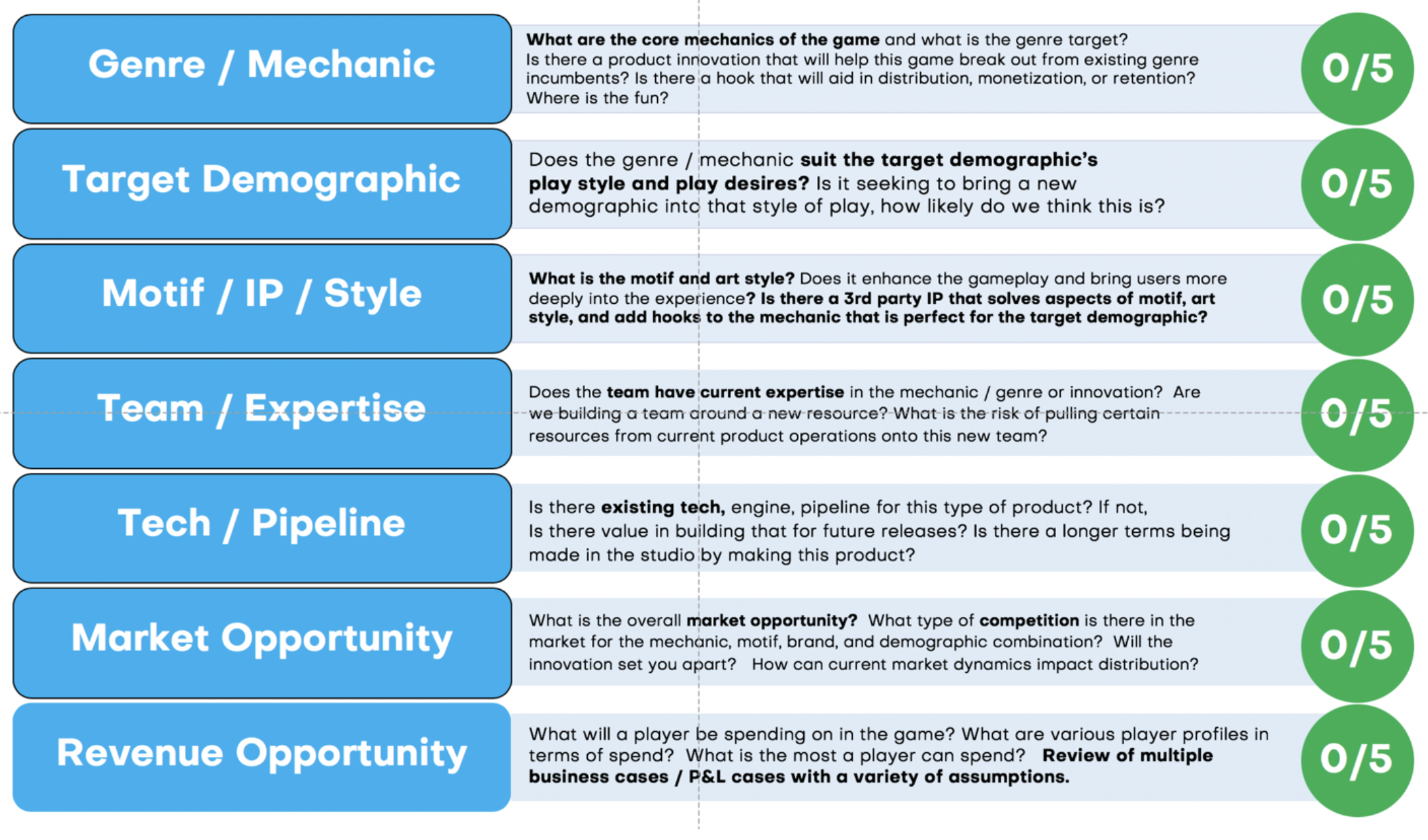

In order to make non-reactive decisions on resourcing a project concept must be reviewed holisticallys, with all relevant stakeholders, utilising appropriate data to drive decisions. Most importantly, greenlight is successful when everyone understands how all of the components of a product concept relate to one another and the strengths and weaknesses created by those relationships. Every company has a different way of doing this, but the below relational matrix illustrates how I make determinations about a product’s overall quality and chances for success.

This matrix illustrates how I make determinations about a product’s overall quality and chances for success.

A game concept can come from anywhere. Standardizing the materials provided for the process is a good start. Some people like to focus on X-Statements, “Reasons to believe” and other positioning, which are important theatrics to a pitch, but at the end of the day the concept really needs to answer:

Who is playing this?

Why will they care?

How is this fun for the target audience? (IP, systems, play)

How do we monetize it? (systems, flows)

Do we have the expertise to build it?

Where does it fit in the market?

Can we distribute it?

What in the design needs to be validated vs. is proven?

How hard do we think that is?

What are we lying to ourselves about?

Creating a scorecard to review is an effective way to bring a subjective conversation about project parameters into alignment. I like to create a set of considerations and rate each one on a 5-point scale, 5 being the highest. More important than the scores themselves is the logic and justification behind them; scoring is a forcing function for critical thinking. If you want to get into more detail, further scoring can break out within each category as well.

Below are the questions to ask of every member of the greenlight team (along with scores) which provide a solid framework for our subjective evaluation of a game concept and its positioning. The goal is to score each individual component of a project, and then break out how the strengths and weaknesses of the project relate to each other. This makes it easy to create a pass / fail condition for a product greenlight, or provides stable criteria you can use to weigh competing projects against one another. These scores should sit on top of all other relevant systems analysis, market, and performance modeling data.

You can then score and discuss the relationships of the above variables under 3 key components to project success:

Once you have a set of informed assumptions and scenarios for the product(as well assupporting financial projections and resourcing models), you have enough data to generate a pass / fail for the greenlight.

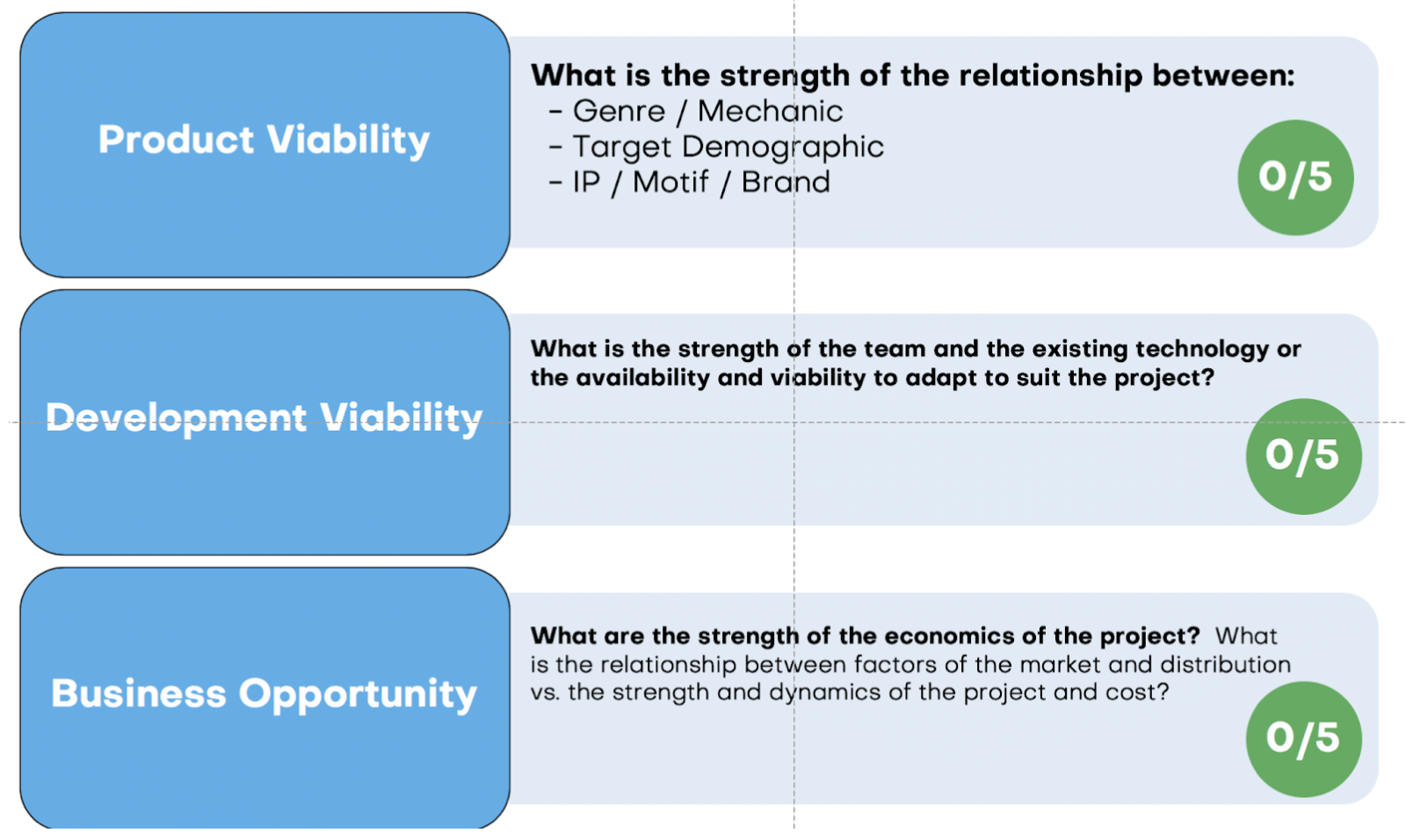

As an example see the below for MARVEL Avengers Academy (Feb 2016):

While at TinyCo, we started the greenlight process for Marvel Avengers Academy as early as 2014. Below is my perspective on that process:

[Note on Revenue Opportunity: I don’t believe we ran a rigorous enough process in modelling based on the initial systems design and didn’t dig enough into what would happen if our demographic assumptions or innovations didn’t coalesce. We ran a variety of rudimentary models to build conviction and ensure we weren’t being irresponsible, but we didn’t do it with nearly enough rigor.]

In today’s greenlight process rigorously analyzing the game systems alongside of all of the other variables to get understanding of player spend and acquisition thresholds is a paramount part of the process.

In this greenlight, I believe we at TinyCo created a narrative for ourselves that sold us on the project.

We saw the relationship between this incredible brand and scale, an opportunity in casual that works well with the type of games we know how to make, innovations that will help drive creativity, a market that will open its arms to the concept for a demographic that wants what we were making. However, we weren’t thorough enough in our evaluation of the opportunity; we found one story that looked great and generated conviction without challenging our narrative. You need to create a variety of scenarios and assumptions, and score each of those scenarios and assumptions separately to look at all the possible outcomes of a project. A good greenlight process should be just as much about finding holes that destroy the narrative of a product’s success as it is about exploring narratives that drive conviction. Without creating and comparing different sets of assumptions about a project, you can end up selling yourself on the wrong projects.

So what ended up happening? In hindsight, we missed the mark in some areas, and nailed it in others

Genre / Mechanic: I don’t believe abstract analogs in an crafting system works. Players fundamentally understand combining bread and cheese to make pizza in a cooking game. Combining fusion generators and plasma to make cosmic substances doesn’t have the same appeal. Materials became payouts in a more basic Narrative Builder loop, which had become a dated experience by the time of launch. Still, we felt our new innovations on narrative, brand, and marketing would help differentiate the game. Alas, our desired product innovations only materialized within events. [My 4 / 5 ended up a 2 / 5]

Target Demographic: We were wrong to assume our casual mechanics and style alone would bring in a female audience. Even though the brand performed incredibly well, bringing in tons of excited players organically our audience was much more male-centric than we told ourselves it would be – even moreso than the overall demographics of Marvel fans. Furthermore, we didn’t have the systems for male players. Our greenlight narrative didn’t take into account the demographics of the existing Marvel fanbase within the mobile gaming ecosystem. We instead let our mechanics and motif alone determine who we thought would play our game. [More of a 2 / 5 than a 3.5 / 5]

IP / Motif: The brand performed very well, and it lent itself perfectly to the universe and brand innovation we created in partnership with the amazing creative team at Marvel. The art style, narrative, universe, and tone was so good that it made up in a lot of ways for a lack of cohesive systems. The world that was created as part of the Marvel Universe was unique, fun, engaging, and was the best part of the experience. The creative team at Marvel are some of the best to work with in games. We were right on the fit here. It was brilliant, hooray! [5 / 5 stands]

Team Mechanic & Genre Expertise: We knew how to build the game, but since we didn’t scrutinize what would happen if we didn’t introduce innovation and how that impacted KPIs, it didn’t really matter that we had the team, we didn’t scrutinize our ability to nail the target mechanic. [The scoring was moot here]

Existing Tech / Engine? Building a 3D pipeline was a great investment for the company, so it ended up working out properly. [Our initial scoring was on point]

Market / Competition? We overestimated the effect that brand saturation might have on the game’s success, Marvel was really smart about windowing and there was plenty of space in the calendar. However, we didn’t foresee how old the game’s core mechanic was to the market by the time of release and how expensive user acquisition would be for this segment of the market (more male more care for a non-core game). The conditions for the genre were the issue and the systems weren’t monetizing high enough to allow for scale. [Given the mechanic, market conditions were more like a 2 / 5]

In the end, the game was well received from a brand and creative perspective. The mismatch in demographic and mechanic, and where the mechanics ended up ultimately held the product back. The key takeaways here are:

You can’t just process and score one level of assumptions during greenlight, you need to insert a diverse set of market data into the process around sizing up a product and where it fits in the market.

You need to generate various cases based on different outcomes that occur during development, or how the product could be received by the target player. You need to take the narrative you have the most conviction around and challenge every aspect of it to see how it stands up to real scrutiny. If we had discussed other less ideal scenarios for the game, we may have rethought the concept or the project in its entirety.

You need very diligent P&L modeling and forecasting with various sets of assumptions that match your score scenarios which is something we should have already had.

How do you quantify the value of a 3rd Party IP

Increasingly non-mobile endemic 3rd party IPs are being leveraged to create massive hits. 3rd party IPs account for about 20% of the Top 300 Grossing games in the USA (not counting event content). Simply put, with the right circumstances, IPs mitigate risk. They have already built a scale of awareness that can positively impact CAC. The brand affinity generates engagement while answering some hard questions about player fantasy, character, world, demographic and art style. A lot of developers in F2P mobile placed big bets on IP over the past 5 years. Some broke market dynamics to create unprecedented success while others crashed and burned (“Designing Women” MOBA anyone?) How do you quantify the value of an existing IP to your business? A combination of scoring a variety of parameters in combination with existing market data. You can create weighting as well to give more critical parameters more relevance. I like to rate each consideration on a 5-point scale, 5 being the highest.

Demographic <> Genre Fit: Does the demographic and game genre match up, or are you forcing fit?

Demographic <> Genre Fit <> Brand Fantasy: Does the brand fantasy enhance and or/ match the demographic and genre fit?

Brand fantasy or desire is defined as: The heart of how fans and die-hards connect around this brand. Some examples:

For Harry Potter it’s the “Everyday Magic” of the world, “Friendships” in a coming of age setting already beset with danger and in need of courage, and “Adventures, Mysteries, and Secrets” awaiting to be unlocked. The core fan fantasy was that everyone just wants to go to Hogwarts.

Mission Impossible would be “Ethan Hunt does the Impossible” beset by intrigue, gadgets, incredible locales and set pieces, within the world of spies twisting the screws on each other. This is almost impossible to make game about unless it was a AAA console action game in the vein of Uncharted.

Bob’s Burgers would be how the humour of the Belcher family and Wagstaff community and the music of the world built on “Family and Community” “Integrity and Individuality” and “The Craziness of Life as an Adventure.” Really with most animation, people just want to spend more time in that world with those characters giving their brand of humor room to breathe within the game experience.

Brand Scale: This is where quantifiable data streams can be introduced:

Box office, TV viewership, International market penetration, merchandising revenues, Facebook audience network data, social media reach, supporting cast reach, Google search, etc.

Brand Relevance: How relevant is this brand to your target demographic? It may be well known or have awareness, but brand fantasy, target demo, and mechanic need to align in such a way that you convince a consumer to spend more time with the brand in your game. Everyone may know who Mickey Mouse is, but in order to capitalise on the scale of awareness of Mickey you need a hook that takes the fun and familiarity of the brand and translates it into a connection that makes sense for your gameplay. Kingdom Hearts and Disney’s Magic Kingdom do a great job of this.

Revenue Strength: Does the brand fantasy drive a F2P mobile game economy? Robocop and other single-hero action films make great movie, but would very hard to create an in-universe F2P game around in any current major genre.

UA Power (CPI efficiency): Will your IP and mechanic get the target demographic to install and engage?

Mobile Saturation: Is the brand saturated on mobile devices? What is in the upcoming pipeline. This is just to view the brand in market context, not the overall project in market context which you’d do as part of the full greenlight.

Partner Risk: What level of resource commitment will you need to provide in order to be a good partner to the brand holder? What additional cycles will be spent, what approval risks exist creatively, and what marketing constraints might exist prior to market validation?

Art Adaptation: Is there additional art adaptation and translation needed to bring the brand to mobile to fulfil the mechanic, demographic’s, and fans expectations, or does it break expectations in an innovative way that drives success?

The more rigorous your understanding of what makes a brand successful for a certain type of game project the less reactive you can be in choosing the right brand for your project. Additionally, by having an understanding of how critical a brand is to your success builds confidence going into a negotiation. You can quantify how far you are willing to go to make a deal happen, or forego one opportunity for another. Creating a profile for understanding a brand’s relationship to a project = deal and further project confidence.

Greenlight in Action

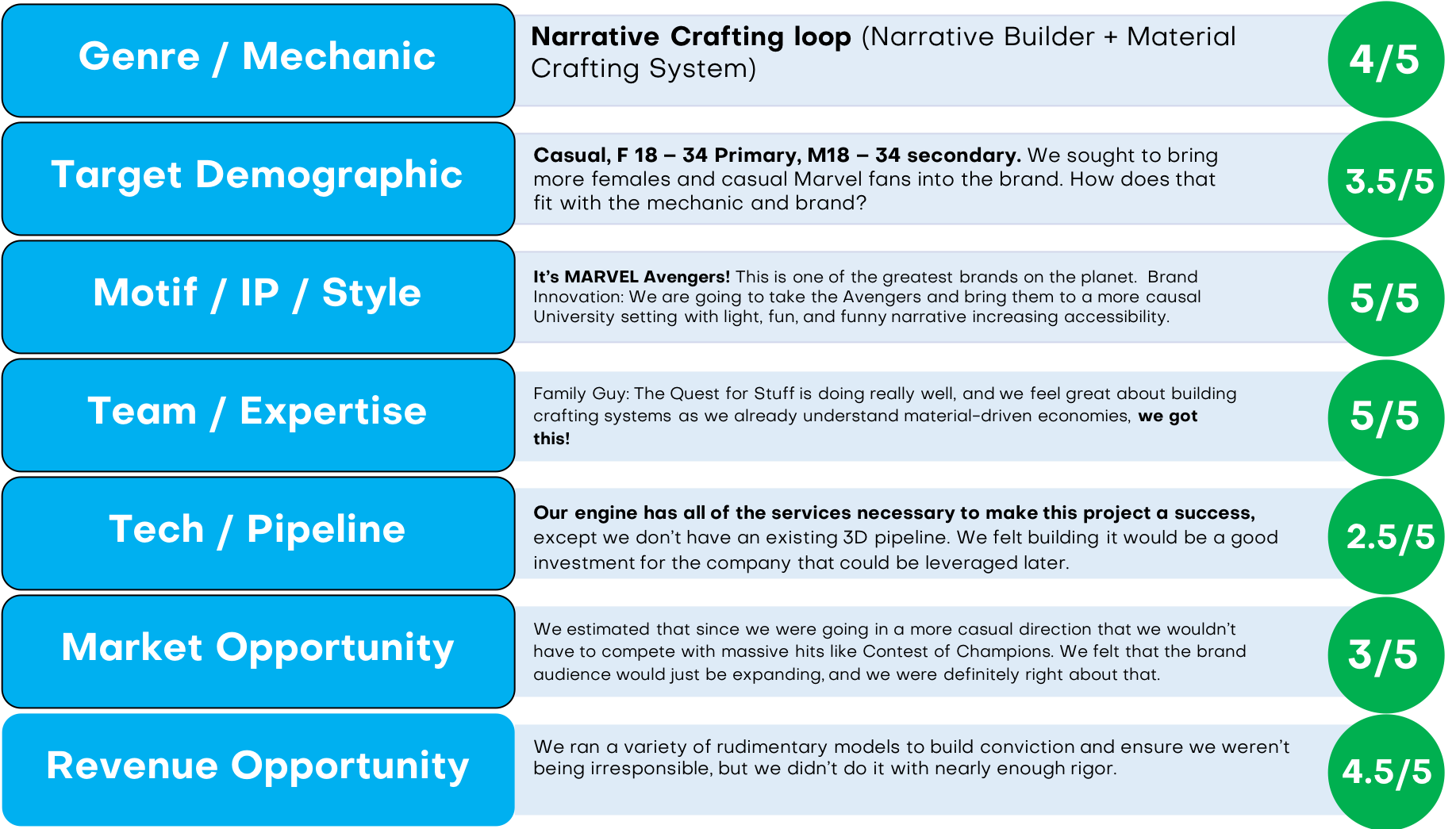

There are 2 recent releases, both based on 3rd party IPs, that I think illustrate where concept and pre-production can go right or wrong.

These two products are Looney Tunes: Worlds of Mayhem, and Disney Heroes: Battle Mode (full deconstruction: Disney Heroes - A Solid RPG That Tests the Limits of an IP). I was not part of the development of either of these games. I never take for granted the difficulties and circumstances of the timing, prospecting, and realities of the business and art of game development. That said, I can see how concept, greenlight, and pre-pro were critical to downstream success or failure here.

Genre / Mechanic <> Demographic <> IP Motif / Brand Fantasy Fit

Both of these projects started with an RPG battle mechanic. Demographics for battle mechanics in mobile games are shifting, but the player profile of a battle-centric RPG mechanic is likely to skew more male and mid-range in age for males, and then younger for smaller segment of females. Taking a more “core” game mechanic and pairing it with a casual, longer legacy, and broad-appeal IP like Looney Tunes or Disney’s legacy animated character roster sounds counter-intuitive. From the jump, both of these projects seem to be taking on of risk. You are going to have a harder time acquiring and retaining the high spenders you want at scale for either of these titles due to that mechanic <> demographic fit being forced. Either of these concept greenlights are being bold by taking such a leap with demographic and brand fit.

Beyond each brand’s demographic’s relationship to mechanic is the execution of the brand fantasy and its fit to the core mechanic. This is where Worlds of Mayhem finds its footing. The Looney Tunes’ brand fantasy aligns much better with a battle mechanic than Battle Mode. Almost every vignette in the Looney Tunes series is about some sort of direct or indirect conflict. There is a lot of direct combat in every show and its visualized in a over-the-top and iconic way. You may not think of combat first when you think of the Looney Tunes brand as a whole, but in the end that direct conflict is a major pillar of these beloved characters and their world. Add to that fit, a single cohesive universe under the Looney Tunes banner, a great roster of characters, and incredible execution of the look and feel (the game looks absolutely perfect, it makes you feel like you’re living the cartoon in game form), you’ve got yourself an incredible and true brand execution that can resonate. On top of those subjective aspects the gameplay is tight and fun, beautiful UI, and thoughtful UX and flourish to deepen the immersion and you’ve got a great product that has a chance to overcome the base demographic <> mechanic mismatch, to what scale is the next question.

Battle Mode starts with the same issues of a brand’s demographic’s relationship to mechanic as Looney Tunes, but its problems deepen when you examine brand fantasy, theming, and art style. These iconic Disney animated characters are incredible, I have a deep love for them as they were a big part of my life growing up. Unfortunately, there is no single brand fantasy here, and no cohesive single universe that all of these characters live in that relate from a marketing and messaging perspective that the market already understands. You’d have to build that narrative and fantasy from the ground up as a totally new IP.

Per Blue tried that, but it wasn’t cohesive, there wasn’t enough time and attention to what that new IP was going to be. Even if you get it right, you still have to invest in that brand over time through mass media marketing, with a huge global marketing budget covering all forms of mass media. Building a connection with a world and characters from scratch via single 1:1 communications via the mobile funnel is insanity mode difficulty.

I can count on my hands the amount of brands competing at scale that started in the mobile funnel - Angry Birds being probably the most well known. You have to explain the brand fantasy and why the player should want it that is hard via performance marketing. Additionally, you have to find a cohesive voice and art style for all of the characters to play together in. You need to make Ralph and Aladdin feel like they should exist in the same context. Even if you were to get all of that right, you still need to connect a core of constant battle to this brand mashup’s fantasy. Ralph fights, the Incredibles fight, here and there a lot of the other characters in Battle Mode fight in their perspective universes, but by-and-large that is not what those characters are about. WALL-E was about longing for love and individuality, Monsters Inc. was about honesty of purpose, Zootopia was about coexistence. As separate worlds, Disney’s characters are about so much more than just winning the fight. Finding a single art style or set of co-existing art styles also starts to diminish the fantasy and immersion here.

Unlike Looney Tunes, Disney doesn’t have a coherent world for all of its characters. Thus PerBlue, the developer of Disney Heroes, had to create a new art style to bring all the characters under same visual umbrella. The change of art style for all the beloved characters decreased immersion and diminished the fantasy.

In Disney Heroes we are seeing a lot of fit being forced rather than being derived from the core tenets of Disney as a brand and these characters as individuals. The brand fantasy, character motivations, universe context, and art style are all being enforced to align with the game mechanics and proposed target demographic rather than the other way around. This misalignment makes it very difficult to communicate a value proposition to consumers that will convince them to spend time in the game. These are fundamental issues with the structure of the product and its relationship to the brand that should be tackled head on in a thorough product greenlight process. No matter how good the systems and economy design are, these fundamental subjective issues will hold the product back.

Even though Battle Mode wasn’t successful in bringing together disparate universes under one banner, this same incredible IP / character set has worked wonderfully for Gameloft’s Disney Magic Kingdoms. This title has fantastic brand demographic <> mechanic fit: casual mass market brands, accessible via casual narrative builder mechanics, in a casual mass market context – the theme park. Additionally, the Theme Park is the universe that all of these characters live in within our imaginations in some way. This aligns with the fantasy of being at a Disney Theme Park where all of these characters do come alive; it’s a place where I want to be immersed with them in a mobile game. The Theme Park is the central character in this game it speaks to me through the characters living and breathing in that realm alongside my gameplay.

Everything conceptually supports the fantasy and the mechanic. It sings. That fit, that intuitive alignment is what makes the beginnings of a project so crucial.

Interestingly, Disney licensed another battle-based brand mashup to Glu with upcoming Disney’s Sorcerers Arena. While I still believe the same demographic <> mechanic issues persist, Glu has already done a much better job with theming and art style than Battle Mode to create a hook that could draw in the more of the demographic that is most likely to convert, and increase the pool of players in the funnel. It contextualises the brand and fantasy very clearly. Through a small differentiation focusing on “sorcery” it creates a more compelling hook for core gamers than a generalized battle.

There is no current game at scale focused on “sorcerer or magic battles.” This tightens the brands ‘ characters fit and theming along with “Arena” for the target demo. Also the art style is just absolutely gorgeous and feels fresh. While there is still the same mechanic <> demographic risk, they’ve done an amazing job at concept and pre-pro to mitigate and are already investing in brand development marketing to make it feel bigger and more cohesive. If they nail the systems and economy, they could see much better performance than Battle Mode.

As these 3 projects are showing, without clear logic and cohesion of a project conceptually at the start and through the early stages of pre-production, you have to fight every step of the way to support and build on a vision that may not make sense. The cracks and cuts will eventually take their toll on product performance.

In Conclusion

Creating a successful F2P mobile game isn’t going to get any easier. If you are going to greenlight a new product, you need the same types of process that AAA console and PC publishers have been applying to their new products for decades. Project greenlight has to be more rigorous than ever:

You must bring the right market data, have all of your parties present, and convert their subjective perspectives and biases into tangible scores.

You must generate a variety of project scenarios and cases, then re-score them to try to destroy your project narrative and find real conviction.

You must scrutinize the relationships between the core building blocks of a successful project. If they don’t relate inexorably, there may be a better project out there.

3rd Party IP’s must be rigorously examined via a similar process that hooks into the overall project greenlight considerations

You must be rigorous about P&L planning with multiple sets of assumptions and scenarios that match your project scenarios.

If you are absolutely ruthless in this process you can more easily compare a variety of projects you may be reviewing and really understand all of the variables that will set you up for greater success. Happy Greenlighting!

*Google “Annorax” and you won’t find a prolific Greek philosopher. He’s an obscure Star Trek villain played by Eric’s dad from That 70’s Show. Apologies.