Star Wars Battlefront II: The Only Analysis You Need to Read

Preface:

The goal of this analysis is not to throw shade at EA / DICE in any way or form. Star Wars Battlefront II is a true masterpiece and a game that every Star Wars and FPS fan should own. Instead, the goal of this analysis is to understand and learn from the mistakes as well as to provide a set of possible solutions on how to introduce microtransactions intoan AAA title.

All the way till launch, Star Wars Battlefront 2 (SWBF2) was a sure-shot and a PR dream. It took the beloved Star Wars license and combined with the prowess of DICE’s Battlefield series. The game had literally no risk as it was the second game in the series’ reboot for the latest generation consoles. Based on the feedback from the SWBF1 DICE not only improved the gameplay but added also iconic starfighter battles and the requested story mode, which spans 3 generations of films. In short, SWBF2 was, on paper, an online competitive first-person shooter built by the best. This notion was further enhanced by the glowing reviews of gameplay coming from alphas, betas and early access.

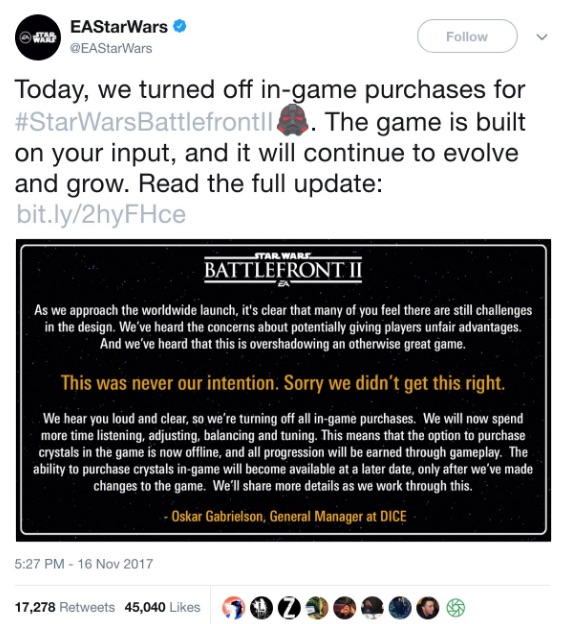

But all of the pros didn’t erase the one critical mistake EA/DICE did with the progression design. By injecting so much importance to their microtransaction-driven gacha mechanic the game was met by full-scale revolt days before the release causing EA to drop the microtransactions from the game completely. A decision which likely meant a loss of around a billion of dollars in digital revenues.

This analysis breaks down why things turned so bad so quickly and how the backlash could have been potentially avoided.

Michail 'Miska' Katkoff - Studio Lead @ Fun Plus

"I would personally love to see EA move towards full freemium model instead of clinging to the old inevitably outdated business model."

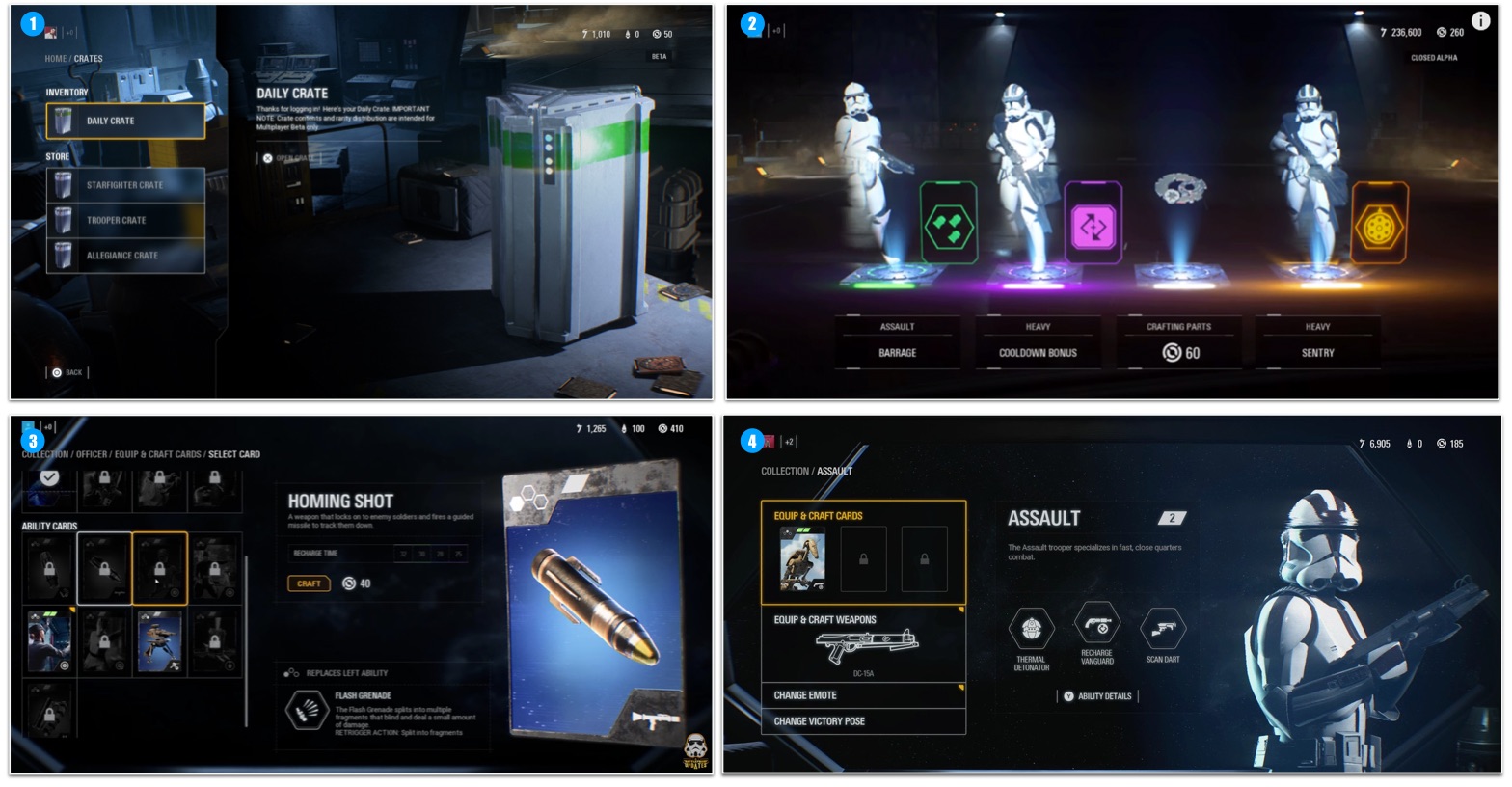

Before diving deeper into analyzing EA’s Star Wars controversy, let us spend a moment on deconstructing the heart of the controversy - the infamous progression design and how the Loot Crates were meant to work.

The player progression in SWBF2 follows two axes. The first axis is Rank of each character player has. Rank increases as the player play the game with that character and gains XP after each battle. The second progression axis is the class specific Star Level, which is a summary of the Star Cards player has for each class or a character. And Star Cards is where things start to get interesting.

The progression design in a nutshell: Players earn Credits by playing matches. Credits are used to purchase Loot Crates. Loot Crates contain Star Cards. Star Cards are equipped on characters to boost or replace abilities. Star Card can be unlocked and upgraded with Crafting Parts.

Star Cards, which player can earn only through Loot Crates, are powerful collectibles, allowing you to boost and assign new abilities to your class and characters. For example, my Stormtrooper’s default ability is Thermal Detonator. I can equip a Star Cards that increases the damage of the Thermal Grenade ability or I can replace the Thermal Detonator ability with an Acid Launcher Star Card. In other words, by boosting and replacing characters’ abilities Star Cards directly affect not only player’s playstyle but also how effective player’s characters are.

The Star Cards come in four rarity level: common, uncommon, rare and epic. The way you get Star Cards is by opening the infamous Loot Crates, which contain common, uncommon and rare cards. Duplicate Star Cards are turned instantly into Credits, which are again used to purchase Loot Crates. Epic cards can be only gained through upgrading the Star Cards player owns. Upgrading requires Crafting Parts, which are also acquired through Loot Crates. Crafting Parts can as well be used to craft any Star Card a player specifically wants.

The way the two progression axis are tied together is that Rank and Star Level act as an upgrade prerequisite. In other words, even if I had an abundance of Crafting Parts, I couldn’t invest these into a new character without first playing with that character and collecting enough Star Cards for that character.

Oh, and the third progression vector is Heroes, Villains and space ships, which are unlocked through spending Battle Points. You'll gradually accrue Battle Points for your in-game actions, but especially for actions like killing enemy players, or completing in-game objectives, like claiming a point for your team.

From the free-to-play perspective, the system design is SWBF2 is quite basic. Player earns Credits and XP (Rank) by playing matches at a rate of 300 Credits per one 10 minute match. Once a player has enough Credits, they purchase a Loot Crate, which cost between 2200 to 4000 depending on the type of a Loot Crate. Loot Crates contain Star Cards and Crafting Parts. In order to upgrade abilities, a player needs both Star Cards and Crafting parts, which pushes them back to playing matches.

The player is incentivized to monetize by purchasing Crystals with real money. Crystals can be used to purchase Loot Crates directly and thus a player can save time by spending real money. Pay-to-Win is countered by requiring a player to reach certain Rank level before upgrading Star Cards for that character. In other words, you have to play with the character you want to upgrade.

The progression system in SWBF2 is not particularly aggressive or grindy from free-to-play perspective. I mean, earning a hero took 40 hours in the first version and was lowered to 15 hours after initial feedback. The issue is that Star Wars Battlefront 2 is not a free-to-play game and thus this system should be reviewed from the perspective of a title that players paid 60 bucks for before even seeing a loading screen.

The way I see it there were two main issues with the progression design in SWBF2:

- The first issue was the player’s ability to pay for content unlock. If it took player 100 hours to earn Darth Vader, Boba Fett or Luke Skywalker in the game, they would have been more than excited to invest that time. The issue is that player can, and are in fact incentivized, to pay to unlock these iconic heroes instantly by opening up their wallets on top of the steep purchase price.

Star Wars is a franchise that is carried by the heroes. I bet every player purchasing the game imagines himself wreaking havoc on the battlefield as Darth Vader. The disappointment arises when after paying 60 bucks player is asked to pay more to play with their favorite characters. Sure, they can play to earn it, but the whole idea of Loot Crates (gacha mechanic) is to distort the investment cost player needs to make to achieve the goal. In other words, you can get Darth Vader in your next Hero Loot Crate or you could not. When it takes about 2 and a half hours of gameplay to earn enough Credits to purchase a Hero Loot crate it is clear that the system is tuned to maximize conversion - or in this case the feeling of getting screwed over.

- The second issue was that the Loot Crate System made the game feel pay-to-win. Loot Crates give players Star Cards and Crafting Parts, which directly lead to significantly improved abilities and tactical advantage. In a full-on multiplayer game, this is dangerous because it makes advanced players even more dominant on the battlefield as they have not only the skills but also much stronger abilities than the players with less time invested in the game.

Star Cards, especially when upgraded to their maximum level, provide overwhelming boost to abilities, which is against the principles 'fair' free-to-play multiplayer game.

Where it turned into straight-up pay-to-win was the fact that players could spend real money to purchase Crystals which they used to purchase Loot Crates and thus instantly improving their characters. This caused the player who didn’t want to pay additional dollars to feel cheated. Every time someone took you down with the same character class you were left in doubt if it was because they had better abilities they paid for. This doubt quickly turned into anger leading players to rage against the EA.

So how EA could have avoided this galactic mess? Well, in my opinion and in hindsight there were few possible solutions.

Blizzard's Overwatch has been extremely successful in monetizing through purely cosmetic items.

1. The Overwatch Model

The straightforward and most player-friendly solution would have been to have the Loot Crates contain only cosmetic items, such as skins, voice lines, and victory poses. In other words, the Overwatch model which has generated well over a billion Dollars in revenue largely due to the players spending money on Loot Boxes in the game. Just think about the demand for various skins for Darth Vader, Chewbacca, Han Solo… The digital revenue of Overwatch would have been peanuts compared to what Star Wars fans would have dished out to customize their favorite heroes.

EA's FIFA Ultimate Team is one if not the most successful drivers of digital revenue on consoles.

2. The Ultimate Tean Model

The more complicated but perhaps better monetizing model would have been adding a new mode to the game that would have utilized the existing progression system. In this multiplayer mode, players would have started from the bottom of the ladder, playing with generic classes and through time and skills progressed towards higher league levels where they could play with their favorite heroes. In other words, this would have been pretty much like the powerful Ultimate Team mode in EA’s top sports games. A mode which is highly competitive and not mandatory at all. A mode that restricts content, which player can access at any time in other game modes. The mode, which is proven and worth 800 million annually and growing!

Wargaming has a great framework for building progression mechanics in free-to-play first-person shooters.

3. Free-to-Play

Finally, EA could have attempted to truly disrupt the FPS market by launching SWBF2 as a free-to-play game. The current progression design is a good starting point for a free-to-play game and with an addition of more rarity levels to the cards and cosmetic items, the gacha mechanic could have easily supported much heavier spending.

The issue of pay-to-win could have been solved with the way Wargaming handles power balancing and progression. In short, this means a Tier based system, where players progress through a carefully crafted tech-tree of playable classes. To better understand Wargaming's progression mechanics, please read the deconstruction of World of Tanks Blitz.

In the end, EA published a paid game that worked like a free-to-play game - and you just can’t have both. I would personally love to see EA move towards full freemium model instead of clinging to the old inevitably outdated business model. I believe that a freemium version of Star Wars Battlefront 2 would have been a genre-defining monster hit instead of an admirable game of the year. Multiplayer first-person shooters rely on player bases for their success and what else could grow your player base that making your game free-to-play?

Anil Das Gupta - Product Lead @ Wargaming

"I can’t help but be totally enthralled by the consumer reaction to the Battlefront situation and the development of free-to-play designs and monetization mechanics being added to Triple-A console games in general. It’s genuinely interesting times for the games industry!"

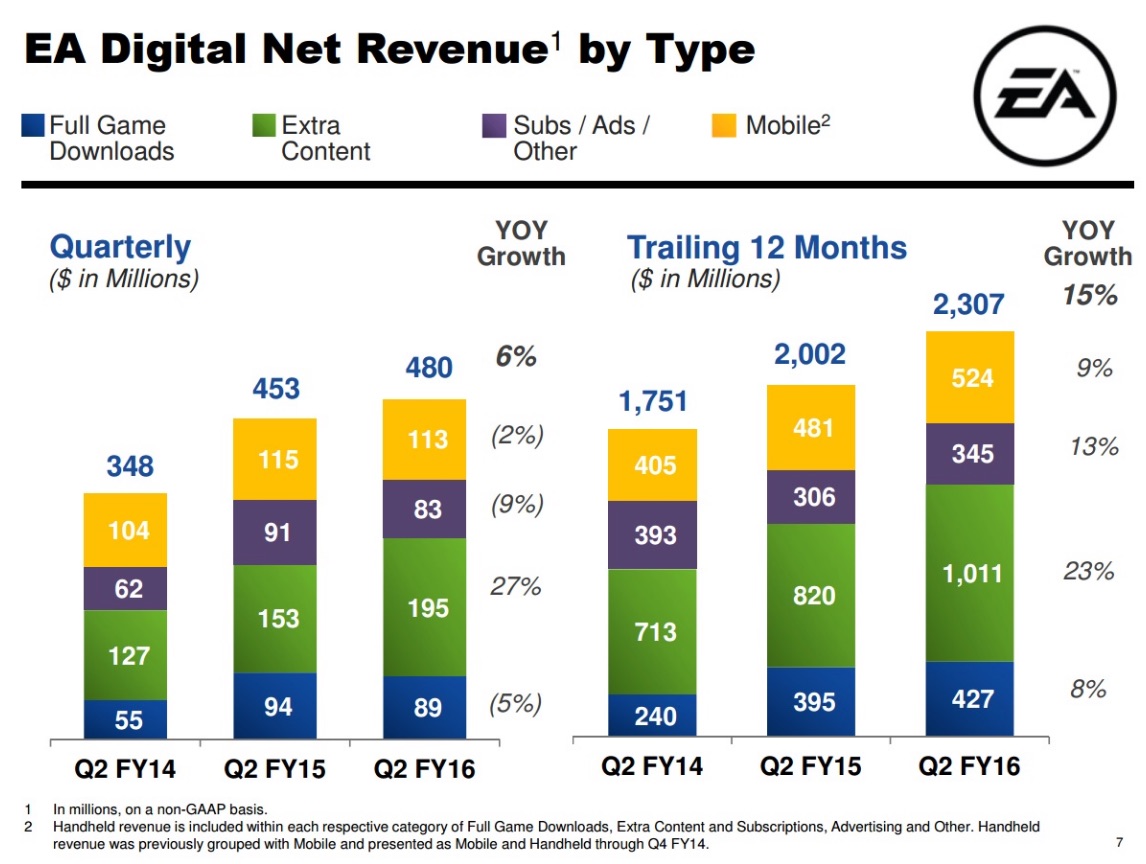

I think that any serious game publisher will be fully embracing microtransactions in all of their games as a result of seeing the success of them in both PC, Mobile and Console titles. For EA, the performance of Gacha systems in FIFA Ultimate Team has added an incredible amount to their topline revenue and which big company is going to leave huge sums of money on the table? Not EA and that’s why microtransactions have been added to this game and likely every other game they will make from here on out.

It’s interesting that the consumer reaction has been so severe given that the system is in place in other EA games. Something that personally makes me chuckle is that it’s been calculated that to get all content in Star Wars Battlefront 2 off the bat, it will cost about $2.2K. And whilst that is a lot of money, I would love to see what would have happened if the game had an almost infinite economy like a 4X game! Games where some players have spent millions of dollars in... Perhaps this is why EA was largely unworried by the development of the system in the game given that it’s fairly light compared to how these systems usually exist in other games.

EA has spearheaded microtransaction monetization on console

The big question here is if microtransactions have a place in premium gaming. As a consumer, I don’t like the idea of spending 60 bucks on a brand new game only to find out I have to spend even more money to get all of the content out of it. If I’m spending that much money up front without being able to sample the game first then it feels like a con to then find out you have to spend so much more. Most other Games As A Service (GAAS) titles could have insane amounts of spending possible, but given that these games can be played for long periods completely for free, it doesn’t feel so bad somehow. PC stalwart titles such as League of Legends, DOTA, World of Tanks and Team Fortress are great examples of titles you can play for years without spending money on. I wonder if SWBF2 had been free to download if the outcry would be so bad? It does feel a bit like EA wants both their cake and to eat it in this scenario, although given the insane numbers posted by Grand Theft Auto V, it’s not surprising they want to follow suit.

I have wondered for a long time about what the end “end-state” for video games will be as I believe more and more games will become GAAS. It means games can be released faster, invested into if they are doing well / cut cheaply if not doing great, and can grow over time. Whereas if you spend a couple of hundred million on a narrative title in the vein of Uncharted, you stand to lose a lot if the title is not successful. Clearly, those titles will still remain popular and there will continue to be a market for them, but as a business, I can see more going down the GAAS route because it allows you to de-risk projects significantly. As a result, I wouldn’t be surprised to see future games from EA be completely free with just microtransactions as a monetization scheme.

NBA 2K18 has a very low user score as a result of microtransactions added to the game. But it has reportedly not harmed it’s performance on the market at all.

Regarding the controversy then, it remains to be seen if the decision to add this element is a good or bad one. It might get massively negative reviews and not sell as many copies out of the gate, but if the systems result in better long-term revenues then it will be seen as a success. A recent example that is worth noting is the one from 2K Games whose title NBA 2K18 had a huge amount of backlash as a result of it’s in game microtransactions, but was called out as having a notable revenue per user in their recent earnings call. In other words, despite all of the complaints, the title is making money for the company.

And ultimately it’s voting with wallets that will truly answer this question. Having worked in F2P for a decade I know that this type of scheme is only going to become more prevalent in all games, because it works. At the end of the day the numbers decide the course of action and I’ll bet that whilst EA might get stung over initial copies sold and a PR backlash, that they will make plenty of money from the game in the background and that they will be able to keep adding content to the game (and thus keeping it profitable) until Battlefront 3 is ready.

Is this healthy for the industry? It probably is, because companies will make more money from their titles which means they can offset the cost (and thus risk) from titles in development through a higher revenue per user standpoint. Is it pro-consumer? Definitely not, and that’s the biggest worry here. The problem is I don’t see how it can be stopped, unless consumers stop buying these titles in the first place, which is not going to happen. Games with huge marketing and PR behind them are always going to make players eager to play and thus I think the model is here to stay. I’d personally prefer it if platform holders such as Sony had some kind of policy in place where a premium game can only have a fixed upper limit of DLC and microtransactions, whereas a free game would not. That would mean that as a consumer I would know what my big money investment would be, or I could play a game for free but know that I am going to have to grind for a long time to get everything. But I just don’t see this happening. Platforms make 30% of every microtransaction so they are not going to enforce things to reduce the money they make! So in other words, embrace the Loot Crate (or Gacha as we have been calling it for the last 10 years) life :/ .

Adam Telfer - Creative Director @ Chatterbox Games

"Especially in games that are PvP, product managers and game designers have to be far more selective about what economies can be impacted by real world cash."

The ecosystem for console games has become increasingly difficult. Games are ballooning in scope, player expectations are higher than ever. AAA Games nowadays are massive. However, the player base which plays console games isn’t growing. Most of the game sectors growth is happening on mobile. Yet the revenue in console continues to grow. The main reason for this is increased digital revenue, mostly coming from microtransactions. Console developers are having to drive more $ per player over reaching a larger and larger audience to cover their costs.

The % of revenue coming from digital content and microtransactions is massive. You can’t ignore the importance as a console developer.

So now console developers are in a really tough spot. Players won’t spend more than $60 for a game. Developers can’t be successful without great reviews coming from hitting all the expectations a AAA game needs to have. In order to cover the costs of development, developers have started to add things like loot boxes and free-to-play economies into their games. But the problem is that they’re still a $60 game. So the design of these microtransactions have to be far more nuanced than a typical free to play game.

Thus far console games have operated on a knife’s edge: each game released with microtransactions has had some backlash from players, but it hasn’t been big enough to impact game sales or counteract the revenue coming from these microtransactions. Slowly over time developers have gone more aggressive their tactics. First adding cosmetics, then adding them to gacha-style loot boxes, then adding low level currency boosts, and finally, a full F2P style economy as in Battlefront 2.

^ Angry Joe is a famous YouTuber that rants about the problems with microtransactions in games. Gamers are savvy. They understand game economies deeply. Games that obviously try to sidestep the issue of microtransactions are always caught online.

Some developers have been smart about how they adopt microtransactions. GTA Online and FIFA opted for a completely separate mode within their game which operate as a F2P economy. Players feel like the $60 paid is for the quality single player content, and the mode with micro transactions is just an optional space a player can play in. When FIFA Ultimate Team was first released, it didn’t launch until many months after the initial launch of the boxed product. Player feedback was positive -- because they felt they were getting additional content for free. Other games avoid selling gameplay impacting content completely. Destiny 2 launched with a gacha that gives very little gameplay benefit at all, avoiding criticisms from fans regarding their microtransactions. EA was not this nuanced with Battlefront 2.

EA launched during the beta of October with loot boxes and progression systems in place. This is when the backlash started, but it wasn’t loud enough for EA to really consider it. Coming around the same time as the backlash of Shadow of War and Forza 7, the backlash was controlled. However, rather than EA dialing back their tactics after the beta, they made minor adjustments. Locking some content until players played enough of the game, and adding some skill-based challenges to reward top end players. This seemed to manage the backlash, despite still having the loot boxes in the game.

What really blew this whole thing up was the locking of heroes. When the game entered its early-access just a few days ago, players noticed they couldn’t play as many of their favourite heroes: Darth Vader and Luke Skywalker. Players paying $60 for the game felt like their progression was being tuned so obviously that no one feasibly could unlock these heroes for months. Polygon even reported that after paying $90 after launch, they still hadn’t unlocked their favourite heroes.

What really blew up the controversy was the balancing for unlocking heroes. To the point that EA dropped their costs by 75%.

This broke a contract with players. Systems in console games that were previously untouched by microtransactions, all of a sudden are steeped in it. In any other battlefield or battlefront game, you’d get this content for free -- or there would be a clear direct progression to it. In Battlefront 2, this was all within the gacha.

This really goes to the core of the problems with Battlefront 2. Its economy was created so that nearly every progression system could be skipped forward by paying. That a player on day one could buy loot boxes, unlock heroes and get to the maximum level without really playing the game. This isn’t good design, this isn’t even good F2P design. The best F2P Games-as-a-service games know this (World of Tanks, Warframe). Their economies push players to play in order to reap the benefits of their payments.

Especially in games that are PvP, product managers and game designers have to be far more selective about what economies can be impacted by real world cash. Doing so not only gives far less backlash, but far greater retention out of your playerbase.

Vinayak Sathyamoorthy - Lead Product Manager @ Zynga

"I think that the core of the issue here is the implicit contract between game developer and game player, and the violation that consumers feel has occurred to break this contract."

Adam mentioned the “contract with players” in his write-up, and that’s what also strikes me about this heated controversy. I think that the core of the issue here is the implicit contract between game developer and game player, (or producer and consumer) and the violation that consumers feel has occurred to break this contract. For the longest time, the contract was fairly clear: game developer took on the job of building a complete entertainment product and put it on shelves for consumers to buy. What ended up on the shelf was the whole entertainment experience - at the time of purchase, the seller had done its job of fulfilling its duties, and the buyer had freedom to consume that experience for however long they chose to do so.

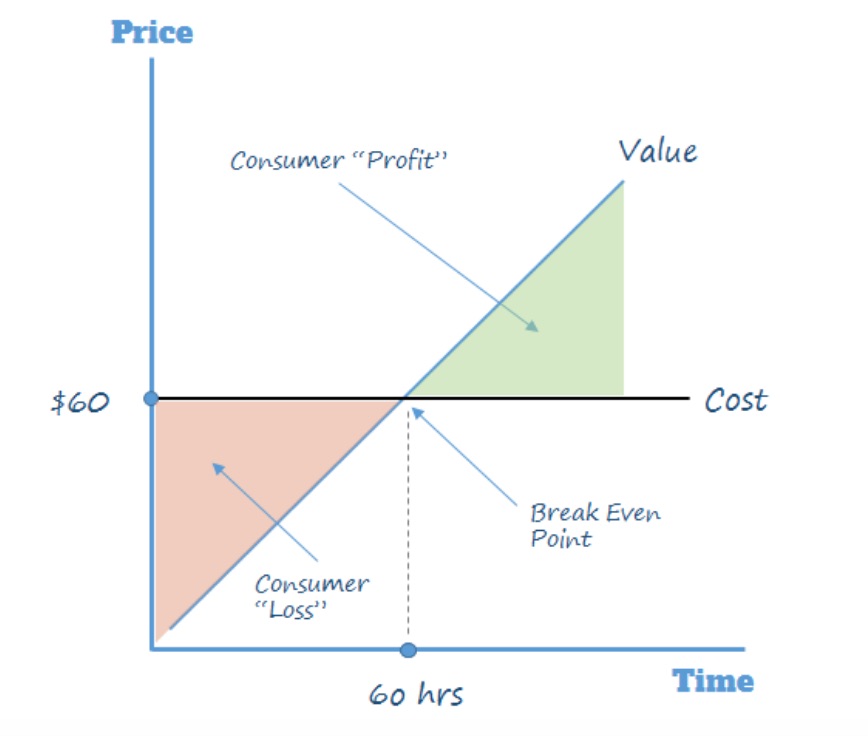

Let’s take a theoretical example of one of these types of games - let’s say I buy the latest Zelda game, and I pay $60. Additionally, let’s say I value 1 hour of entertainment at $1. If I get 60 hours worth of entertainment, I “break even”; meaning that I feel like I got my money’s worth. (see graph below) Until then, I’m experiencing a consumer “loss” - but as soon as I reach the break-even point, any additional amount of time that I play that game I experience a consumer “profit”. I’m getting more than I bargained for, which is the ideal state. The gold standard games that we all love would break this barrier and provide us with an abundance of profit.

I pay a fixed cost of $60 to buy a game, but the value that I get increases over time. The old school model of games.

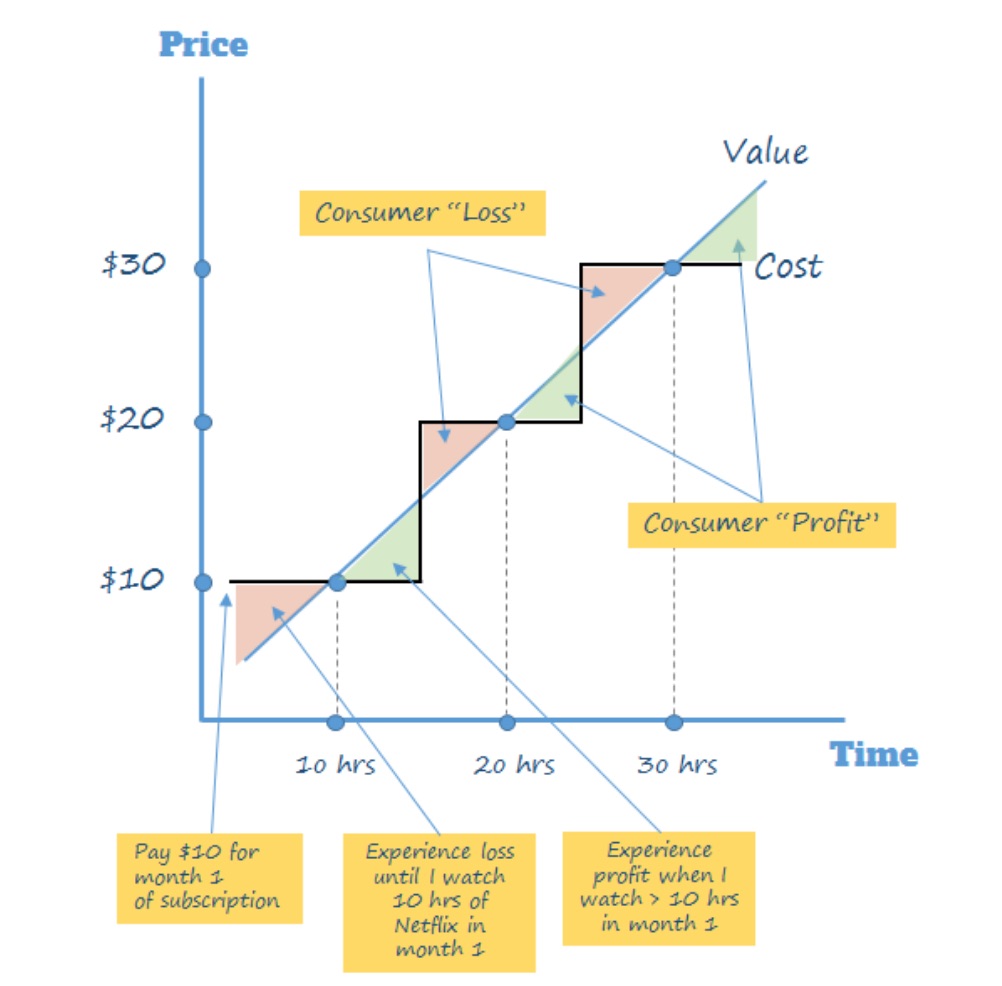

Before I get to the freemium model, let me briefly describe a relative of the freemium model: the subscription model. Let’s take Netflix as an example - Netflix charges me a fixed price for their service per quantity of time. For the sake of example, let’s say I spend $10 / month on Netflix. As in the prior example, let’s say I value 1 hour of entertainment at $1. I break even when I consume 10 hours of Netflix per month. Anything more than that in a month, I’m getting a surplus, or a profit - see figure below. The step function increases in cost correspond with the monthly fees - in the figure below, you pay $10 month, and over 3 months you pay $30. Similar to the above model, there is a “fixed cost”, but in the subscription model that occurs per unit of time. I can watch Netflix 24 hours a day, 30 days a month and pay the same as watching it for 1 minute a month.

I pay a fixed cost of $60 to buy a game, but the value that I get increases over time. The old school model of games.

Freemium games totally changed the business model, and with it, changed the contract between game developer and game consumer. In this model, the contract was also fairly clear: game developer shipped a product and made it available to the consumer, but they would additionally continue to iterate on that product, and the job was never really done. The consumer has the option to consume that product in a completely free way - there is no necessity to transact at all. However, should they want the premium experiences associated with the product, they then transact with the producer, and thus the microtransaction was born. The contract here also is very clear that the transaction does not entitle the user to the complete experience or product - the consumer only gets incremental pieces of the product with the transactions.

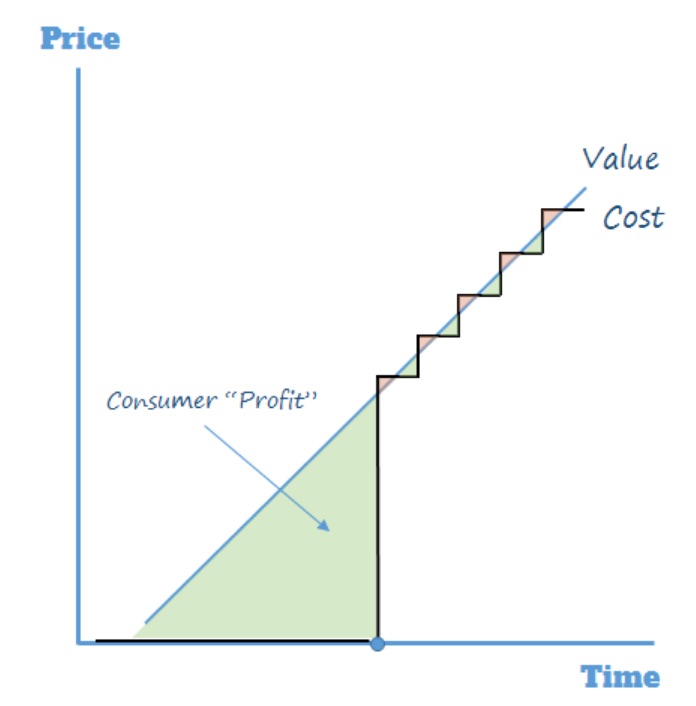

Let’s take a look at what the model looks like in freemium - it looks a little like the subscription model, but with the big caveat that the consumer pays nothing up front, and receives profit up front. As we all know, you can (and the vast majority do) play freemium games free forever. But, on an aggregate level, consumers pay for the product. The reason that this model works is that a large group of users can play for free because a very small percentage of players pay a lot. Through microtransactions, users essentially “subscribe” to pieces of the product, but unlike subscriptions, the cost can scale very high. Cost is not distributed evenly - imagine if you could watch Netflix for free, because a few users spent a million dollars a month on it, and that’s what we’re talking about!

I get an abundance of consumer profit in the beginning with a free-to-play game because the cost to me is zero. However, as I progress I get pinched and I end up paying. At an aggregate level (i.e. across all players) users are paying for the product after trying it for free. Users get all consumer profit up front, but the profit is then split between consumer and producer later.

In the best examples of this model, the relationship between consumer and producer is also mutually beneficial (it provides a profit to both consumer and producer), and the consumer can feel the surplus from getting the value that exceeds the price that they paid. I can personally attest to this, and I will also note that I have happily paid for EA free-to-play titles and enjoyed the value I received from them. I also feel that many consumers would agree with me that when you are able to experience a product for an extended period of time in a freeway and feel that you are getting value, you are willing to pay to get the best of what it has to offer.

The violation that consumers are feeling is with Battlefront II is that EA is eating into their consumer profit by extracting more value from them. EA’s approach in this instance was to take both monetization models and their equivalent pricing and expect consumers to react favorably. See the figure below - by using a hybrid model that combines pricing from the old school model with freemium microtransactions, EA runs the risk of making consumers feel cheated because they are losing a huge chunk of their profit.

Compare the “Old School Games Model” (left) and the “EA Battlefront II Model” (right) to see where consumers are getting angry. You get an abundance of consumer profit on the left; you are squeezed heavily on the right.

To put the figure above into numbers - if I expect 60 hours of entertainment to break-even on Battlefront II, and upon completing that I have to keep paying, I might end up feeling squeezed from the profits that I expect to receive.

As others have stated, we react this way when things change from what we are used to. We are accustomed to AAA console games giving us full experiences because we paid up front. We have expectations when we pay $60 up front. EA hedged their bet on this one - they want the upfront revenue of a $60 game, AND they want micro-transactions to work. If they went all-in on microtransactions, they could have charged significantly less upfront; maybe this would have been more palatable as a $20 game that had microtransactions. Or if EA was clear about what users would need to pay for with microtransactions (and what they didn’t need to pay for).

Ultimately, I believe in games-as-a-service, and I expect EA to invest more heavily in this strategy. I think it provides value to consumers and producers, but it needs to be done in a way that meets consumer expectations. The problem here lies in our expectations and the feeling that consumers get when they feel producers violate that contract between the two parties.

Alex Collins - Gameplay Engineer / Lead Designer @ Fun Plus

"Whereas outsiders may look upon the situation from a calm, logical, and informed perspective, the influencers in the heart of the crowd seem to be anything but."

In-app-purchases in console/PC games have always been a sticking point with the consumer, but never have I seen an implementation enrage potential buyers so overwhelmingly as with SWBF2. Especially in a case where, perhaps, the intentions were not the most misguided. While it cannot be denied, as many have said, that EA attempted to have its cake and eat it too in terms of gating hero unlocks beyond the initial purchase price of the game, I believe their misconceptions about their audience go even deeper than that. It seems that it wasn’t just that the unlocks and upgrades were gated that offended the SWBF2 fanbase, but what effect the progression would have on their match-to-match experience that enraged them and helped fuel the intense backlash the game has received.

Traditionally, console and PC gamers are notoriously hyper-competitive, often to the point of intense toxicity. In any competitive multiplayer game on these platforms, you will see many players who invest emotionally into the game, doing whatever they think is necessary to win. When left unchecked, this behavior can lead to an infestation in the minds of the players known as the Dunning-Kruger effect, a phenomenon in psychology defined as:

A cognitive bias wherein people of low ability suffer from illusory superiority, mistakenly assessing their cognitive ability as greater than it is.

In practice, this bias can be seen affecting people at almost all levels of their respective competitions, video games or elsewhere. It is important to note that “low ability” is a relative term in this sense -- somebody can actually be quite objectively skilled in a certain activity, but still be limited because think they are much better than they actually are.

The Dunning-Kruger effect describes the path of anybody learning a new skill, following them from their point of lowest wisdom to their highest enlightenment.

Over the years, I have observed many (many many) people who have suffered from the Dunning-Kruger effect - myself included. It makes you do things that, looking back, you cannot believe you ever thought were appropriate or necessary. One of the most telling signs that somebody is overestimating their own skill is their unwavering belief that when they lose, it is never, and I mean never, their own fault. Defeat is due to their allies making poor plays, their enemies getting lucky, the game rules being broken, or any other litany of wild and untenable reasons, as opposed to the player’s own numerous mistakes. In other words, you don’t know what you don’t know, and it’s not until you realize how much you actually have to learn and take responsibility for your own shortcomings that you’re able to really grow and progress.

And so it is this all too familiar rhetoric of worrying about losing that jumps out to me as I read and listen to commentators discuss the design of SWBF2’s progression. Whereas outsiders may look upon the situation from a calm, logical, and informed perspective, the influencers in the heart of the crowd seem to be anything but. What started initially as dissatisfaction that characters were being locked behind a grind escalated into pandemonium as people realized what this could mean for the game’s competitive matches. Without hesitation, they brutally cursed EA for making the game “pay-to-win”, and outright ignored EA’s (admittedly poorly worded) response that they were trying to increase the longevity of the content and give players a sense of accomplishment for their achievements in the game.

After the annoyance that the most beloved heroes are not available from the onset, the most common complaint I’ve seen is that you can’t tell if your opponents “earned” their gear without involving their wallet, or if they just paid to unlock it instead. Having played dozens of mobile F2P games, I know from experience that it is rare this dynamic really becomes an actual problem in terms of game balance; many games are designed to work around these concerns since if they didn’t, both payers and non-payers would probably have a poor experience and quit. If more players had actually gotten their hands on SWBF2, perhaps they would have seen this in action, but as the uproar from the community was deafening and relentless, the paid loot crates have already been removed and we’ll never know.

In Clash Royale, you’ll lose a lot, sometimes to people who clearly have dumped $100s more than you have into the game. And that’s okay, because they’ll move up out of your league so you don’t have to play them anymore.

Even games created by some of the most beloved and highly-regarded developers in the industry, such as Blizzard and Bungie, are not immune to their communities constantly questioning (if not blasting) their ability to balance their games. Though in each of their biggest games the way you gain power is totally different, they all approach in-app purchases in the same way: by selling purely cosmetic items and repeatedly assuring their players they will never jeopardize competitive balance with their monetization. As I described above, this may not be a concern in reality, but it is critical that you sacrifice some earning potential in order to not be crucified by your players, no matter how much clout you have. EA wanted to make more money by bending these rules, and pretty much everybody freaked out at the prospect of the game being horribly imbalanced and therefore essentially ruined from the get-go.

And this leads back to what everybody in this article has discussed - while EA may have had a solid logical, financial, and analytical reasoning for their decisions, they terribly misread the way that their audience works, and are now paying a heavy price for doing so. This is not the F2P world where people are willing to give games a chance even if there might be pay-to-win elements, and it’s not a new IP where people are still discovering who their favorite characters are. If EA wanted to increase their earning potential, they needed to follow the proven examples on the market, not try out something risky with this massive license. These Star Wars fans don’t mess around; they want their Luke Skywalker and their Darth Vader, and they want them now!

In all seriousness, EA’s consumers are not dumb - their immediate reaction to the tactics employed by SWBF2 shows us this for certain. But they also seem to be a little more confident in their own knowledge than they should be, and it is in this regard that I believe EA dug their own grave. They appear to not only have underestimated their players’ ability to recognize the goals of SWBF2’s design (make a bunch more money for EA), they also overestimated their players’ ability to fully understand how it would affect them in the competitive arena (probably not very much). When combined with the frustration of not being able to play their favorite characters without a massive grind, EA created a hurdle for themselves that was essentially impossible to overcome. In a way, EA’s massive success with FIFA Ultimate Team may have made them overconfident in their own understanding of these intricacies, leading them to fall victim to Dunning-Kruger as well!

Where EA goes from here should be very interesting, and will tell us a lot about how much, or how little, they’ve learned from this fiasco. Will they turn IAPs back on in a couple months once the controversy has died down? Will they introduce skins and other cosmetics as an alternative to powerful gear unlocks in their loot crates? Or will they just give up on adding paid loot crates entirely to focus on their plans for the next Battlefront game? Regardless, EA has a long way to go in recapturing the trust of the massive Star Wars fanbase, and the story of SWBF2’s launch will live on in infamy for years to come.

Thanks for reading and please, leave a comment below on what happened and why it happened. Do you think EA do the right thing in pulling out the microtransaction and how will this affect monetization design in AAA games in the future?